To the surprise of many experts, the IARC classified cell-phone-radiation exposure as 'possibly carcinogenic to humans'

What gives cancer its awful power is its mystery. For thousands of years, there was virtually no mention of the disease in the nascent medical literature because we could not see it, could not recognize our cells rebelling against us. Even though doctors began to understand the nature of certain cancers — and then began reducing death rates through better screening, drugs and surgery — the essential enigma of the disease has never been resolved. Nowhere is that more the case than with brain tumors, which remain as deadly as they are rare. Lung tumors and other cancers can be blamed on lifestyle factors or environmental triggers, but aside from a few statistical quirks, there is little explanation for why a brain tumor strikes one patient and spares another. So if you were that unlucky one, wouldn't you grasp for any reason that the "emperor of maladies" — as oncologist and author Siddhartha Mukherjee calls cancer — had come for you?

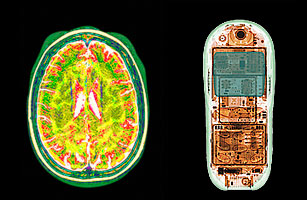

That desperation helps explain why the question of a possible connection between cell-phone radiation and brain tumors remains so heated for a handful of scientists and a larger group of activists and victims. For most cancer experts and medical organizations, it's an open-and-shut case, and cell phones have been exonerated. Radiation is considered potentially carcinogenic when it is powerful enough to ionize atoms or molecules — adding or removing a charged particle. Nuclear decay and X-ray radiation are known ionizers — and known carcinogens — able to rip molecules to shreds and cause genetic damage that leads to cancer. Cell-phone radiation is non-ionizing and thus considered too weak to cause such damage.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the National Cancer Institute, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and countless other bodies have agreed that cell phones are safe to use. On the World Health Organization's (WHO) website for "Electromagnetic Fields and Public Health: Mobile Phones," you can read the verdict in black and white: "To date, no adverse health effects have been established for mobile phone use."

But those first two words may be key. At the end of May, 31 scientists from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) — the WHO body that does what its name says — spent a week reviewing the latest studies on cancer and cell-phone-radiation exposure. And to the surprise of many cancer experts, IARC classified cell-phone-radiation exposure as "possibly carcinogenic to humans." The panel put cell phones in category 2B on the agency's willfully unhelpful scale, below sure carcinogens like cigarette smoke and in the same category as the pesticide DDT and gasoline-engine exhaust. "A review of the human evidence of epidemiological studies shows an increased risk of glioma and malignant types of brain cancer in association with wireless-phone use," Dr. Jonathan Samet, the chairman of the IARC working group, told reporters the day the study was released.

For those who had been sounding the alarm on mobiles, the IARC verdict was a moment of vindication. Last year Devra Davis — an award-winning environmental epidemiologist and the author of The Secret History of the War on Cancer — dived into the cell-phone scrum and produced a new book on the subject: Disconnect. She argued that the wireless industry had all but suppressed any evidence that cell phones might be dangerous, controlling research by controlling funding just as the tobacco industry had for decades. "The world is not fair or just on issues that affect a global multitrillion-dollar industry," Davis wrote in an e-mail to TIME. But the IARC results, she suggested, could begin to change all that.