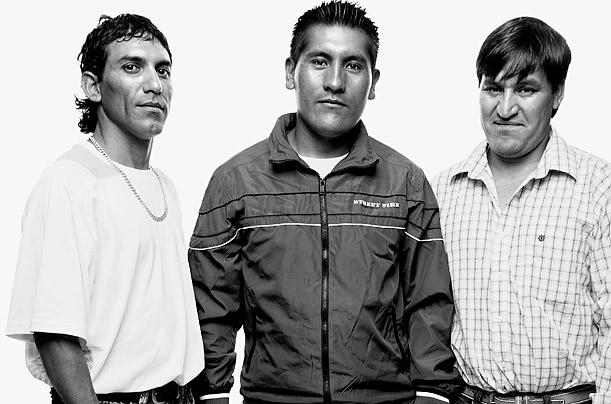

Chilean miners (l to R) Claudio Yañaez, Carlos Mamani, Osman Avaya

There is no ear in the earth to hear my sad moaning

Abandoned in the middle of the infinite earth! —Pablo Neruda

When we meet Mario Sepúlveda in the Pacific Coast city of La Serena, Chile, in November, it is 1 a.m., and he is running laps around his hotel pool. Like many of the other 32 miners who were rescued in October after 70 days trapped beneath Chile's Atacama Desert, Sepúlveda, 40, still has trouble sleeping. "I only get three or four hours a night," he says. It might be because of the memories of waiting 2,300 ft. (700 m) underground for 17 days before officials located the miners, when the specter of starvation or even cannibalism haunted each man, or it could be that their biological clocks are still set like those of subterranean bats.

The insomnia is a reminder that los 33 — whose miraculous survival and rescue this year inspired a world desperate for a happy ending to something, anything — haven't yet completely emerged from their dark abyss. Yet this is as good as it gets for mining dramas, as recent tragedies, from the U.S. to New Zealand and especially China, where 1,261 miners were killed in just the first half of 2010, make all too starkly plain.

Why did things turn out so blessedly different in Chile? A mother lode of luck and faith was involved. But the rescue also showcased a commodity even rarer today than the gold the miners were quarrying: leadership. "We made sure it was one for all and all for one down there," foreman Luis Urzúa tells us. After the San José gold and copper mine collapsed on Aug. 5, forcing the men into an emergency shelter, Urzúa's avuncular guidance kept them alive for more than two weeks with just two days' worth of food. Chilean President Sebastián Piñera tells TIME that while he was grateful for U.S. help — it was a Pennsylvania team that eventually drilled a shaft to retrieve the miners — he also had learned from America's dawdling responses to Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf oil spill. Advisers warned Piñera that the miners were probably dead, but, he says, "I decided we had to act immediately and, as a society, play for life."

Urzúa was most sorely tested when the miners suddenly heard search drills just meters above their heads and then just as suddenly heard them go silent. "To have that much hope turn into that much despair — that was worse than dying," recalls miner Daniel Herrera, 27. Urzúa agrees. "I realized we were a needle in a haystack," he says. "It's then that you have to convince them not just that they're going to survive but why they have to survive — their families, their faith."

Probes found the miners on Aug. 22. That's when Piñera, 61, a conservative billionaire whose brother was a minister under the 1973-90 dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, and Urzúa, 54, who hails from a poor mining family and whose leftist stepfather was murdered by Pinochet henchmen, bonded over rescue plans. "We were very direct and frank with each other," says Piñera, who insisted Urzúa address him with the familiar tú rather than the more formal usted. The night of Oct. 13, they stood together after Urzúa, the last miner to be freed, was brought up in the rescue capsule.

The miners have since been welcomed from Beijing to Broadway, and they're learning to cope with their newfound fame — to handle finances, endorse products and negotiate deals. But what many say they'd like more than anything is a good night's sleep.