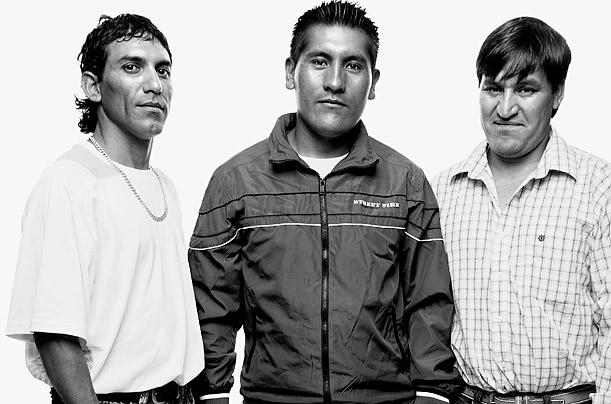

Chilean miners (l to R) Claudio Yañaez, Carlos Mamani, Osman Avaya

(3 of 3)

Q&A with Chilean President Sebastián Piñera

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera spearheaded the rescue of 33 miners trapped 2,300 feet below the Atacama Desert for 70 days. A conservative billionaire who has governed Latin America's most developed country as a moderate since taking office last March, the Harvard-educated Piñera, 61, spoke with TIME's Tim Padgett and Anthony Esposito at the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago:

TIME: What drove you to get to so personally involved in the miners' rescue?

PIÑERA: When the [San Jose gold and copper] mine collapsed on Aug. 5, I was on my way to President Santos' inauguration in Colombia. I apologized to him and returned to Chile, to the mine. It was apparent the mining company was too small, with no capacity to carry out a search-and-rescue mission; so I decided, either the government does it immediately, with total commitment, or it will be too late. And we would seek out the world's best help, including the U.S. I recalled how much time was lost in the [U.S.] response to [Hurricane] Katrina arguing over who was responsible and who wasn't, and the same thing happened with the [Gulf] oil spill. First you solve the problem, and afterward you identify those responsible and punish them.

TIME: Did you really believe that the miners were still alive under more than 2,000 feet of collapsed rock?

PIÑERA: My own advisers told me, "Don't get too involved in this — this is going to end badly." And in fact, the history of mining accidents is brutal; the immense majority end with everyone dead. But I had a profound personal conviction, an inner voice, that the miners were alive. The [miners'] families transmitted that faith as well. This was about the value we assign human life. So I told them, "We're going to look for these men as if they were our own sons." I decided, as a society, that we were going to play for life.

TIME: You were at the mine when the men were finally located.

PIÑERA: On Aug. 21, my wife and I were with my father-in-law, who was dying of cancer. He was an engineer and knew a lot about mines, and he told me that night, "They're alive, we're going to find them, don't give up." The next morning, Aug. 22, he died, and my wife told me to go to the mine. So I went, and that afternoon, after 17 attempts to locate the miners with drilling probes, we found them with the 18th. I keep the message they sent up — Estamos bien en el refugio los 33 (All 33 are OK in the emergency shelter) — in my office.

TIME: You're a billionaire, from a conservative, pro-business party. Could you really relate to working-class miners and their families?

PIÑERA: I grew up middle class. My father was a public functionary who didn't leave an inheritance, just debts. Luis Urzúa [the miners' foreman and leader during their ordeal] and I were very direct and frank with each other — sometimes I spoke by phone with him from here in the palace — and I insisted he address me as [the familiar] tu instead of [the formal] usted. We had some disagreements, such as how fast we should be moving the rescue. But he achieved real leadership of the group below, and I owed him my respect.

TIME: There were reports that you actually wanted to go down into the mine yourself during the rescue.

PIÑERA: I thought about it, but I knew my job as President was at the surface. I'm a person with a lot of affection for adventure — I scuba dive, skydive, fly helicopters. But my wife told me, "Don't even think about it."

TIME: The rescue also pointed up how shameful miner safety still is in Chile. Did you get so involved with this in part to prove the compassionate conservatism that you pledged in your presidential campaign?

PIÑERA: This year was our bicentennial. In my campaign we proposed a grand mission to make Chile, by the end of this decade, the first country in Latin America to escape the underdevelopment that has trapped us for 200 years, to create a society of genuine opportunity for everyone. The first pillar of that project is a revolution in the quality of our human capital, like education reform and radical labor reforms to create a new culture of worker safety.

TIME: Chile has an impressive economy, but can it really become a developed country as long as it has one of the region's widest gaps between rich and poor?

PIÑERA: No. We also need a new culture of worker dignity, starting with closing the giant gap between the richest and the poorest, so we don't have people living on two distinct planets. Aside from labor reforms, we're pushing for income tax reform and getting our business owners to see that we need not only innovation from them but social responsibility as well.

TIME: Two decades after the end of the right-wing Pinochet dictatorship, under which your brother served as a Minister, Chile remains politically polarized. Has the rescue helped break down the sharp divide between left and right?

PIÑERA: Chile was indeed a tremendously divided society during [the Pinochet] era, which lasted almost 20 years [1973-90], and our government aspires to overcome it. The miners meant unity for everyone here. We found that united we can achieve great things, that this bicentennial generation can realize the dreams our grandfathers never could — and rescuing the trapped miners is one example. That said, we also received generous help from many, many countries. I would like to thank the U.S. government and the U.S. people [for one].

TIME: Compared to Brazil or Argentina, foreigners know little about Chile except its wine. Will that change now as well?

PIÑERA: I think this has been extremely good for Chile's image. We never in our wildest dreams imagined being present in the world in such a positive way. Chile is perhaps not as well known because it was forged in an atmosphere of difficulty. Early on it wasn't a rich viceroyalty like Peru or a giant like Brazil; it was a poor, remote captaincy, buffeted by nature and very isolated from the world.

TIME: Chileans, perhaps as a result, can seem reserved and aloof to outsiders. Did the miners show the world a more outgoing side of the Chilean character?

PIÑERA: I will admit that the exuberant personality of [miner] Mario Sepulveda, for example, is not very common in Chile. But yes, I think we're seeing the emergence of a more audacious, happier Chilean character, and that's a good thing.

TIME: Should the miners be TIME's Persons of the Year?

PIÑERA: I really think they deserve it, because they gave a very good example to the world, fighting for their lives united, with faith and courage. [They demonstrated] that we can achieve goals that to other people might appear impossible. I think the world is a better place because of them. Normally, big news is bad news, but in this case it was very big news but also very happy news.