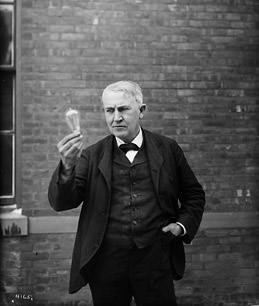

The great man regards his most famous invention

On Sept. 8, 1878, Thomas Edison journeyed to the Connecticut workshop of the inventor William Wallace to examine Wallace's prototype for an electric light. A reporter from the New York Sun tagged along. Edison had begun thinking about the problem of electric light. What drew him to Connecticut was Wallace's "arc light" system, which consisted of a steam-powered electric dynamo that pulsed current through two tall carbon sticks to create an eye-searing beam.

"Edison was enraptured," reported the Sun. "He ran from the instruments to the lights and from the lights back to the instruments." The Wizard of Menlo Park recognized the immense possibilities in the new dynamo. He also understood the limited prospects of the arc lights it powered, which had been developed in the early 19th century but produced light so bright they were usable only outdoors or in large interiors.

Giddy with excitement, Edison turned to Wallace and made a bet: "I believe I can beat you making the electric light. I do not think you are working in the right direction." Edison rushed back to his "invention factory" in Menlo Park, N.J. The race was on.

Because he had a peerless inventive mind, it would be a race that Edison would win. He would do it by perfecting an alternative to harsh arc lighting, one that other inventors had struggled with — the incandescent bulb, which sends a mild electrical current through a thin filament that gives off a gentle glow. But Edison's triumph as an inventor would also demonstrate his perennial limitations when it came to fulfilling the market potential of his inventions.

A mere week after his visit to Wallace's workshop, Edison summoned the same Sun reporter to Menlo Park, where he proudly revealed an amazing breakthrough: the first practical incandescent bulb. (What he did not mention was that its filament burned out after an hour or two.) Moreover, he promised that his revolutionary light was but one component of a far larger dream: a whole system of electrical power. "I can light the entire lower part of New York City," he declared, "using a 500-horsepower engine."

But first he had to perfect that tricky bulb. It would take years of experimenting with platinum, paper and bamboo before Edison found his way to a durable filament, carbonized cardboard. And there remained the problem of developing a workable generator and a system of electrical transmission. So it would not be until Sept. 4, 1882, four years after announcing his discovery, that Edison finally stood before a crowd in the Manhattan offices of the investment firm Drexel, Morgan & Co. and threw a switch. All around him, 100 incandescent lights glowed to life, using power generated by the new station his team had built on nearby Pearl Street. In downtown offices and stores, another 300 new Edison bulbs shone softly.