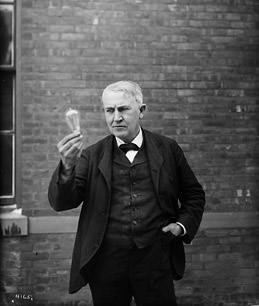

The great man regards his most famous invention

(2 of 2)

To Edison and his Wall Street backers, this was but the beginning of a lucrative empire of light and power. But competitors were lining up. The most formidable was the industrialist George Westinghouse, who doubted the prospects of Edison's low-voltage direct-current (DC) system for the good reason that DC-generating plants could not transmit electricity economically more than half a mile. In 1885 he snapped up the patents for a radical new European technology that used alternating current (AC) to transmit high-voltage electricity over great distances. By late the following year, Westinghouse was showcasing his new system at a department store in Buffalo, N.Y. But the high voltage of AC carried risks. Edison wrote darkly to one of his top executives, "Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size." Moreover, DC systems could be used to power motors. No one had figured out how AC could do that.

Nikola Tesla, one of the world's true eccentric geniuses, hoped to solve that problem. A Serb from Croatia, Tesla had studied electricity in Austria, then went to work for the phone company in Budapest, where he suffered a nervous breakdown. Soon after, during a sunset stroll, he had an almost mystical vision of a working AC-motor design.

That was in February 1882. Two years later, after a stint in Edison's Paris office, Tesla was in New York working directly for his idol. But after Edison told him that there was no future in "deadly" AC, Tesla started his own arc-lighting company, hoping to earn money to develop the motor himself. By the end of 1887, Westinghouse and his AC system had become Edison's biggest competitor. Pressed on all sides by top associates, Edison reluctantly acquired patents for a European AC system. As for Tesla, in 1888 he finally unveiled his AC motor. By July, Westinghouse had purchased all of Tesla's AC patents and hired him to create a commercial version of his motor.

Over the next several years, there were rumors of a possible merger between Edison General Electric and another rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Co. Edison always dismissed these, but the matter was not truly in his hands, not so long as the bulk of his company's shares were controlled by the financier J.P. Morgan. On Feb. 5, 1892, Alfred O. Tate, Edison's personal secretary, was at his desk in the Edison Building in lower Manhattan when a reporter came in to tell him that Morgan was about to announce the merger — a development Edison knew nothing about. A few months earlier, Thomson-Houston president Charles Coffin had shown Morgan that his firm had almost twice the profits that Edison General Electric did. Convinced that the difference was due largely to superior management at Thomson-Houston, Morgan decided that Coffin would run the merged firms. Worse, Morgan erased Edison's name. The new company was to be called, simply, General Electric.

Later, Edison expressed his bitterness to Tate, vowing to do something "so much bigger ... people will forget that my name ever was connected with anything electrical." Of course, nothing of the sort happened. But though we live now in a mostly AC nation, it's Edison's name we revere. It was his genius that launched the electrical revolution, and his lightbulb illuminates our world to this day.

Jonnes is the author of Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World