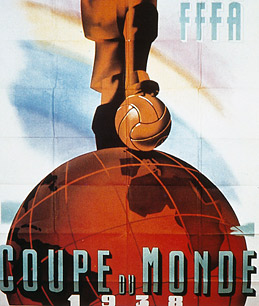

Official 1938 World Cup Poster

At a party in 1998, João Havelange was asked whether he considered himself the most powerful man in the world. It was a question suitable for a head of state, but Havelange, who was merely the president of FIFA, or Fédération Internationale de Football Association, soccer's governing body, didn't blanch. He said, "I've been to Russia twice, invited by President Yeltsin ... In Italy, I saw Pope John Paul II three times. When I go to Saudi Arabia, King Fahd welcomes me in splendid fashion ... Do you think a head of state will spare that much time for just anyone? That's respect. They've got their power, and I've got mine: the power of football, which is the greatest power there is."

Now, 12 years later, on the eve of World Cup 2010 in South Africa, FIFA and its showcase quadrennial tournament are more powerful than governments or the multinational corporations that queue up to sponsor the games. FIFA was laughably late to tap the reach of mass media, but in the past two decades, it has fully harnessed the technological and marketing powers of a global economy. The World Cup has become such a force that it triggered a cease-fire in a brutal civil war in Ivory Coast, caused stock markets of losing nations to tumble and catalyzed a spike in the birthrate of the 2006 host, Germany. How's that? Hosting the World Cup allowed Germans to express a nationalist spirit that had been understandably dormant for 60 years. They felt the love, apparently.

When FIFA's juggernaut opens in Johannesburg on June 11, it will be South Africa's turn. The rainbow nation expects nothing less than a reaffirmation of its nationhood and the chance to inform billions of television and Internet viewers that the host country represents the thriving future of the continent.

FIFA planted the idea for an international championship at its first meeting, in 1904, but it wasn't until 1930 that it bore fruit. El Campeonato Mundial de Football was hosted by Uruguay, officially in honor of the nation's independence centenary but actually in honor of its willingness to single-handedly cover the tournament's organizing costs.

As the World Cup struggled to find its feet in the postwar years, its biggest boost came in the form of the still nascent technology called television. From 1954 to 1986, the number of TV sets worldwide increased more than twentyfold, from a little more than 30 million to more than 650 million. "The world united by a ball" — once a World Cup motto — was now a world united by the tube.

FIFA's first attempts to cash in on this phenomenon were none too remunerative. In 1954, the European Broadcast Union televised live nine games from the World Cup in Switzerland to neighboring countries, paying nothing for the privilege. However, a marked spike in TV purchases was noted, a hint of the existence of a market eager to consume live soccer.

Just as a Brazilian wizard named Pelé helped change the way soccer was played, so on the business side, Havelange, an entrepreneurial Brazilian who became FIFA president in 1974, would change the way it was paid. Havelange gradually shifted FIFA's TV-rights deals from broadcast cooperatives, which paid very little, to privately owned broadcasters. Initially, the broadcasters reaped major profits from selling advertising during the live telecasts of the games.

Several of these deals under Havelange ended up in the hands of supporters like Horst Dassler, an heir to the Adidas sporting-goods fortune, who had helped Havelange gain office. Dassler had set up his own company, International Sport and Leisure (ISL), which specialized in the nascent business of reselling the broadcasting rights and pocketing a nice markup in the process. This system of corporate patronage would be perfected in the 21st century by Joseph "Sepp" Blatter, a protégé of the duo since joining FIFA in the mid-'70s. Blatter took over the presidency in 1998 and set to work cutting FIFA in on plumper deals.