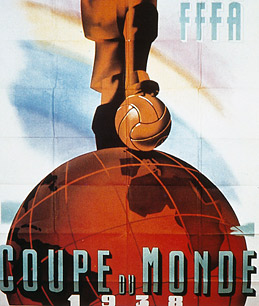

Official 1938 World Cup Poster

(2 of 2)

How central did television become to the World Cup? For starters, it changed the traditional evening kickoffs to maximize European TV ratings. In Mexico in 1986, games kicked off at noon, despite temperatures in some of the venues that topped 100°F (38°C). Argentine star Diego Maradona, who would lead his country to the title, fronted the players' protests, claiming the kickoffs were "ravioli time, not soccer time." The porcine Maradona, then playing for a club in Italy, clearly relished his pasta — but television prevailed.

Blatter made the game truly global, taking it to Asia and Africa, following Havelange's trailblazing decision to stage the 1994 World Cup in what was seen as the soccer desert of the U.S. The still unsurpassed success of the U.S. tourney allowed Blatter to float TV packages for the 2002 and 2006 tournaments to the highest bidder on a country-by-country basis. Under Blatter, FIFA began soliciting only the biggest brands and corporations, and all rights packages and sponsorship deals were sold for two World Cups at a time, guaranteeing fees against volatility in the global economy. The packages don't come cheaply: in 2006, Blatter enticed more than $875 million from FIFA's top sponsors.

Ironically, one casualty in this money-spinning era was FIFA's chosen marketing partner, ISL. It may have practically invented the sports-marketing model, thanks to Havelange and Dassler, but the niche was soon a crowded one. In 1995, ISL surprisingly lost its grip on the rights to the Olympics and was forced to make a dizzying array of wild acquisitions to compensate. Desperation prevailed over strategy, and ISL went bankrupt in 2001.

ISL's bankruptcy was a huge embarrassment that put FIFA deep in the hole, since it was no longer receiving the many tens of millions in rights fees it was owed. Blatter crafted a solution, which included a securitization tied to future earnings, that sustained the organization's cash flow. But his deputy, Michel Zen-Ruffinen, then acting as FIFA general secretary, was convinced that the ISL-FIFA relationship was doomed by corruption, not a dubious strategy. He presented his evidence to Blatter and the FIFA board, alleging that his boss had committed fraud. Some board members backed him, and Swiss prosecutors leveled fraud charges against Blatter, but the case was eventually dropped. Blatter proclaimed his innocence throughout, saying the accusations were lodged to prevent his re-election. Zen-Ruffinen was soon out of FIFA, and Blatter was re-elected president. Since then, FIFA has knuckled down to business relatively scandal-free, although the 2010 World Cup is not without blemish. It has been revealed that resale rights of ticket and travel packages were awarded to a Swiss agency, Match Hospitality, that is partly owned by a company fronted by Blatter's nephew Philippe.

Blatter, it could be argued, has been too successful for his own good. In early May, rights-protection manager Mpumi Mazibuko announced that FIFA had launched 2,500 legal actions designed to stop unlawful use of its brands and trademarks — some 450 in South Africa alone. Despite it all, FIFA has shown record profits year after year under Blatter's stewardship by using market power and the power of the World Cup to seduce the global sports audience.

South Africa 2010 represents a test for the business model that has produced FIFA's vast profits. There have been concerns about safety, security, price gouging and foreign attendance. The tournament will cement Blatter's legacy one way or another, but it is unlikely to weaken his viselike grip on power. With a recent proposal to limit presidential terms rejected by 15 votes to 5, Blatter's opponents in FIFA have been marginalized. "We are comfortable." Blatter said recently. "I would not say we are rich, but we are happy."

David Hirshey and Roger Bennett are the co-authors of The ESPN World Cup Companion, published last month by Ballantine/ESPN Books.

— With reporting by James Tyler