Champion Material

Amnat Ruenroeng, who learned to box while in prison for robbery, won early parole in January 2007 because of his fighting prowess. Amnat is now a member of Thailand's Olympic team

She was on fire. She was on ice. When your whole body has been rubbed with menthol balm, it's hard to know whether you're hot or cold, but that sensory invigoration was just what Thailand's Siriporn (Samson) Thaveesuk needed to take the Japanese girl. The venue for the World Boxing Council (WBC) light-flyweight world championship bout was the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces stadium in Phnom Penh, paint peeling, bleachers sweaty-slick with nervous punters, the smell of dope in the air. Samson's opponent had a career in advertising before turning pro, but the Japanese knew how to punch efficiently and cleanly. With her pink boxing gloves, Samson hunkered down for 10 rounds. The boxing was workmanlike: jab, hook, upper cut, jab. No floating like a butterfly, barely a bee sting. When the fight was finally called on points in Samson's favor, the 25-year-old beamed briefly then spent the rest of her victory parade looking relieved. Boxing to Samson was a way out, just like selling methamphetamine was supposed to be a path away from poverty. Dealing "crazy medicine," as meth is known in Thailand, had landed her in jail. Boxing had freed her.

If every global sport has a narrative, boxing's is a tale of redemption. With each teeth-jarring blow and flutter of feet comes potential salvation. Cassius Clay fought for black pride and transformed into Muhammad Ali. In an earlier era, Joe Louis had floored Max Schmeling to expose the lie of Aryan supremacy. For others, boxing has offered a literal escape: Sonny Liston earned early parole from an armed-robbery conviction because of his A-bomb jab.

Drug dealers in Thailand aren't supposed to get second chances. Some things Samson couldn't help, like being born into a dirt-poor family in the central Thai province of Lopburi. Then again, some Thais believe Buddhist karma deposits people in a slum for a reason. Samson's father left when she was little. Her mother died on the job, powering a stunt motorcycle up a Wall of Death. Some choices, though, were Samson's own, like dropping out of seventh grade and trying brightly colored tablets of crazy medicine. Using led to dealing. Dealing led to a 10-year prison sentence at age 17. Four years in, Samson signed up for a new prison boxing program, partly to alleviate the boredom of life in jail, partly to learn how to defend herself from other inmates. Each day, she changed out of her orange jumpsuit and studied the sweet science in a makeshift gym located on the fringes of a factory where prisoners sewed clothes.

Calling her a quick study would be an understatement. In April 2007, less than three years after she first entered the ring, Samson won the vacant World Boxing Council's light-flyweight title against a Japanese fighter. The contest was held in a Thai prison, and Samson entered the record books as the first world champion to claim her title in jail. Two months later, Samson was released early on parole for good behavior — a euphemism for having fought her way out of prison. Her accomplishment was just one of dozens of world boxing titles claimed by Thais. Steeped in a local tradition of kickboxing, known as the art of eight limbs, Thais have seamlessly transferred that skill to international boxing. Eleven of the country's 17 Olympic medals have come courtesy of the sport. Since leaving prison Samson has defended her title three times, most recently in Phnom Penh on April 26 against the Japanese boxer. The date also happened to be Samson's birthday. "I've really made it," she said after the bout, with more than a touch of wonderment in her voice. "I never thought my life would turn out like this."

With 170,000 people behind bars in a country of 65 million, Thailand has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. The majority of prisoners are drug offenders, many first-time felons who in other countries might have gotten off with a warning or stint in rehab. Cells are so crowded that inmates are sometimes forced to sleep sideways instead of on their backs. In such an environment, any diversion is welcome. The Thai prison system began its formal nationwide boxing program five years ago, inviting both international and Thai kickboxing coaches to train inmates. "The one thing people in detention have a lot of is time," says Wanchai Roujanavong, director general of Thailand's Department of Corrections. "It's a good environment for dedicating yourself to boxing." The sport also provides postprison opportunities. "A lot of people have a hard time finding jobs after they are released," says Wanchai. "But in boxing, no one cares about your history."

Lord of the Ring

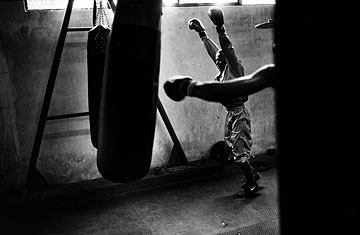

The slab of concrete hidden behind thick walls and loops of barbed wire at the Central Correctional Institute for Young Male Offenders may be the largest boxing gym in the world. For six hours each day, 160 wiry, lavishly tattooed, thoroughly badass looking prisoners spar and attack punching bags with a single-minded determination that underlines how high the stakes are. Many gifted pugilists have been released early on parole. Those who are still incarcerated but have fewer than 42 months left of their sentences can box in outside fights and keep their prize money to buy prison perks, like shrimp chips or enough space to sleep on their backs. According to prison officials, not a single boxer released from detention there has landed back in jail, compared to at least a 10% recidivism rate among the prison's general population.

For all the sweat and testosterone, the young-offenders gym is a peculiar place, because it's missing the edge of aggression you would expect in a boxing ring, not to mention a prison. Inmates finish pummeling each other and then deferentially bring their hands together in the traditional Thai greeting. Voices are gentle. One of the best boxers, a bantamweight nicknamed Black Lion who has already fought in 30 outside bouts, points out his favorite tattoo. It says "Mam." It's dedicated to his mother, though he's embarrassed that the English word is misspelled. "I have disappointed her for so long," he says. "I only finished first grade. I took drugs. Maybe with boxing and good focus, I can fix myself and make my mother proud."