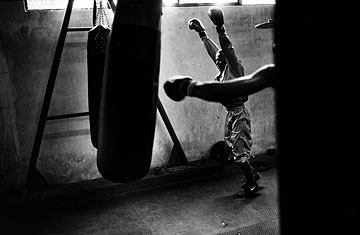

Champion Material

Amnat Ruenroeng, who learned to box while in prison for robbery, won early parole in January 2007 because of his fighting prowess. Amnat is now a member of Thailand's Olympic team

(2 of 2)

Amnat Ruenroeng can't make amends with his father. He didn't make it to his dad's funeral, because he was too high — on heroin or crazy medicine or something else, he can't remember. Of all the mistakes the 29-year-old has made — beating up his first-grade teacher, snatching necklaces and wallets, robbing houses of everything including their fittings — missing his father's cremation is his biggest regret. Amnat is the ninth of nine children. His parents sold pigs, and all his other siblings now sell pigs, but pigs just weren't Amnat's thing. So he stopped school in second grade and apprenticed himself to a Thai kickboxing gym. At 7 years old, he lost his first fight and cried from the pain in his ribs. He lost his second bout, too, but at least he stopped the tears from flowing. The years after that were a blur of highs and lows: well-aimed kicks that placed him among the top kickboxers in the region, drug-fueled robbery sprees that landed him in jail three times.

Then, in 2006, Amnat decided to try his hand at international boxing. Having barely cracked a 15-year robbery sentence, he figured it would be a good way to pass time. A year later, Amnat had won a national title in the 108-lb. (49 kg) light-flyweight division. Not coincidentally, he was paroled the day after that January 2007 fight — just two years and six months into his sentence. Last November, Amnat captured a bronze at the 2007 World Boxing Championships in Chicago. He's now on the Thai Olympic boxing team, which has been training in Vietnam to avoid, as one coach puts it, "girls, nightclubs and other distractions." Amnat's Cuban coach Omar Puentes rates the former prisoner a medal contender in Beijing. "The discipline and dedication that he got in prison are what account for his success," says Puentes. "He's got more discipline than anyone else I've trained." Amnat is even more direct: "If I wasn't a champion, I'd still be in jail. That makes me try very hard."

The boxing narrative doesn't always end with redemption in the ring. Witness former world heavyweight champ Mike Tyson's slow-motion self-destruction: the rape conviction, the bizarre facial tattoo, the ear he chomped during a 1997 title fight most everyone knew he'd lose. Out of the ring, pugilists can be unprepared for the pitfalls of fame. Convict boxers are more vulnerable than most. A stranger comes and promises you a second chance — who would turn that down?

In Thailand, for women jailbird boxers, Chuwong (Eddy) Toomkit is your man. Eddy favors dark suits, even when the mercury rises near 104°F (40°C). His hair is dyed as black as his clothes. Eddy speaks English with an American twang and claims that Samson has about $15,700 in the bank, courtesy of his promotional prowess. (Some boxing insiders have hinted that Samson's success owes more to Eddy's ability to land her big fights than any proven track record.) Eddy also says that since TIME's policy is not to pay for interviews, he won't allow Samson to talk to the magazine. Is this what Samson wants? "She trusts me on everything," he says. "I do everything for her." Asked, when Eddy isn't around, what kind of savings she has, Samson says she has no idea. "Eddy knows all that," she says. And in Phnom Penh, the boxer admits she has no idea of the amount of the purse she just won. "Eddy doesn't tell me things like that," she whispers. "You'll have to ask him."

But for a girl who went to jail at 17, Samson's fairy tale continues. After her successful defense of her world title in Phnom Penh, the birthday girl went for dinner at the Thai ambassador's house. Imagine: a convicted drug dealer dining with diplomats and generals. She gave a speech and teared up. So did the men in suits and uniforms.

Fighting to Live

There is another Thai ex-jailbird boxer who desperately wanted to be in Phnom Penh. Two years before Samson won her first title, Wannee (Nongmai) Chaisena made headlines when she fought a world championship straw-weight (105 lbs., or 48 kg) bout while in jail. A prison band cheered her on, but she succumbed to a technical knockout in the seventh round. The result wasn't surprising: Nongmai had only been boxing for a year and had never battled more than three rounds at a time before the championship contest (title fights are 10 rounds). Nevertheless, Nongmai was released 18 months early from prison.

Nongmai had been busted with hundreds of tablets of meth — her fourth arrest and third stint in jail. At 17, she had been working at a Toshiba TV factory and decided to put a little of her bonus toward a card game. A couple hours' diversion turned into a 10-day gambling spree. Somewhere along the way, someone convinced her to chase the dragon to stay alert. By the end, Nongmai had just 60 cents of her $770 bonus left. Toshiba fired her for skipping work. Crazy medicine was what carried her through.

Now 29 years old, Nongmai knows she doesn't have much time left in her boxing career. Illness kept her from the Phnom Penh card, though she plans to fight again in July. Nearly half of her friends from jail, she says, have ended up behind bars again. Others walk the streets instead of dealing. Nongmai doesn't want the same fate. So she has taken her boxing earnings — Eddy is also her promoter — and bought a small convenience store in Bangkok. In the evening, she sells chicken satay to passersby, most of whom have no idea that the petite grillmaster happens to rate in the top echelon of the WBC rankings. Unlike Samson, with whom she's close, Nongmai knows exactly how much is in her bank account. In addition to the store, she has also purchased a flat-screen TV, oversize speakers and a motorcycle. Her dreams are just big enough to encompass a Honda Civic — in white.

There's a searching quality to Nongmai, in the way that she bounces her legs with frenetic energy, in the rapid up-and-down glance she uses to assess strangers. "When I was in prison, I had the gift of time, and I used it to train a lot," Nongmai says, wearing a shirt emblazoned with the phrase FIGHTING SPIRIT. "But now, it's more difficult. There are so many things to do." Boxing got her this far — and for that she's grateful. But bouts end after 10 rounds. Life has a way of carrying on.