Of all the weapons brandished across the East-West divide after WW II, history has largely ignored furniture and fashion. But the soft power of armchairs, washing machines and ceramics gets its due in "Cold War Modern: Design 1945 to 1970," an exhibition now on at London's Victoria and Albert Museum that "views the history of modernism through the lens of the Cold War," says co-curator Jane Pavitt.

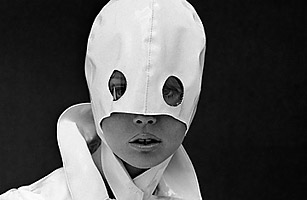

It may have begun as an ideological battle, but the emergence of a Cold War domestic front was epitomized in 1959 when U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon visited Moscow with a model home boasting all the modern conveniences any decent, hardworking American family could aspire to. In reply, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev promised, "the Soviet Union will overtake America and then wave bye-bye." It never did — at least not in household goods — but "Cold War Modern" shows how the two power blocs traded on the propaganda potential of art and design; how artists from Picasso to Rauschenberg subverted the rhetoric of peace, war and nationalism; how posters, film and photos fostered the spirit of revolution that roiled the world from Cuba to Prague; how the space race and nuclear paranoia became stylized in films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Dr. Strangelove, firing the minds of fashion designers and finally entering the living room in the form of plastic armchairs and high-tech gizmos.

Though the Cold War lasted another 20 years, the exhibition stops at 1970, the point at which, says Pavitt, "art and architecture become more radical ... when faith in the future, utopianism and technology get burned out." When, some might say, designers got out of the kitchen in search of something cooler.

— BY MICHAEL BRUNTON