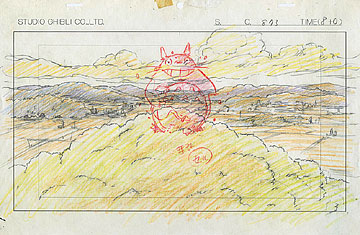

IMAGINATION AT WORK: Each layout contains the gist of a shot

Given the vast forest of layouts that Studio Ghibli has produced since its establishment in 1985, it is a wonder that anyone was able to select the mere 1,300 on show until Sept. 28 at Tokyo's Museum of Contemporary Art, www.mot-art-museum.jp. But select they have, and like the Japanese animé house's best work the exhibition is thoughtful, multilayered and deliciously whimsical.

Even if you haven't heard of Studio Ghibli or its fabled animator Hayao Miyazaki, chances are you'll recognize the work when you see it. Studio Ghibli's better-known films — feature-length charmers like My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Princess Mononoke (1997) or Spirited Away (2001) — share a hand-drawn naturalism, grace of motion and attention to detail that have become exquisitely rare in a world where virtually all animation is digital.

While computers are sometimes used — digital paint was employed in Princess Mononoke, for example — the essence if not the entirety of a Studio Ghibli film still consists of Miyazaki personally putting pen to paper. His latest fairytale, Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea, which grossed over $91 million in the first month of its Japan release, was done entirely by hand. The power of this as a means of differentiating Studio Ghibli's work from other animation houses cannot be overstated. Characters and story lines, too, are seemingly inimitable. "The Ghibli working style is possible because of Miyazaki," says animé expert Ryota Fujitsu. "No one can copy it."

That much is apparent at the exhibition "Studio Ghibli Layout Designs." While layouts — which are not simple frames but elaborate, annotated illustrations that contain the instructions for a whole sequence of frames — have long been a feature of the industry, Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata took them to a far higher level of complexity, beginning with the drawings for the animé series Heidi, Girl of the Alps in 1974. Today, layouts serve to convey the composition of shots, character positions, scenery, follow-through action, camera angles and more, for takes no more than a couple of seconds long. They are created so that artists on the animation assembly line can understand exactly what is required from each animation cell and illustrated background.

Hard-core Miyazaki devotees will make a game out of seeing what they can recognize — from the wildly cluttered wizard's bedroom in Howl's Moving Castle to the dishes eaten by Chihiro's parents in Spirited Away (the fateful meal causes them to turn into pigs). But neophytes can get just as much satisfaction from the dynamic quality of the drawings. The opening sequence of 1984's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (a Miyazaki-Takahata film that predated the foundation of Studio Ghibli) is there as a lush forest drawn from high above, with blocks of clouds marked A to D — an instruction to the assembly line to animate them in that sequence, at a speed carefully specified on one of the clouds. In another layout, the camera swoops before Ashitaka from Princess Mononoke as he gallantly draws a bow at his enemies while riding a giant antelope. The image falls somewhere between reality and magic, which was probably the intention. "There is reality in the fantasy created by Studio Ghibli," says Ryusuke Hikawa, an animé critic for over three decades. "But their message is that daily life is also full of wonder."