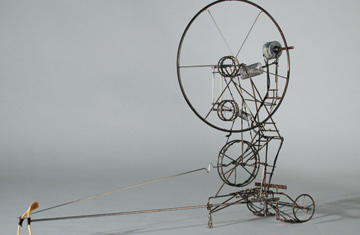

A MOVING WORK OF ART: Ganson's Machine with Wishbone

There have been times when kinetic art — think of Marcel Duchamp's spinning bicycle wheel screwed to a stool, Alexander Calder's abstract mobiles or the self-destructing machines of Jean Tinguely — moved the art world. Recently, though, it has tended to be sidelined as the work of toymakers and garden-shed boffins, finding a warmer welcome in the science museum than the art gallery. That's no bad thing, to judge from "Fantastical Mechanisms — Machines Tell Stories," the biggest exhibition of its kind in Europe since the '60s, on show at the dashingly futuristic Phaeno science center in Wolfsburg, Germany until June 29.

An hour's ride by high-speed train from Berlin, the Phaeno has assembled 70 contemporary works that show the range of emotion and ingenuity of kinetic artists. They have at least one thing in common: "They're all completely obsessive," says Sarah Alexander of Cabaret Mechanical Theatre, a museum of automata that brings its showcase of 10 British artists, including Paul Spooner, to the Phaeno. The inspiration for Spooner's witty, handcranked wooden tableaux can be an artistic masterpiece — as in his saucy version of Manet's Olympia — or the odd mental image of a man eating the bathtub of spaghetti in which he's sitting. "It's the challenge of getting the thing to work that makes them get up in the morning and go to their sheds," says Alexander.

Gone are the days when the inner workings of automata were hidden to preserve the magic; the cogs, cams, pulleys and levers at "Fantastical Mechanisms" are all part of the show. American artist Norman Tuck offers practical but surprising demonstrations of scientific principles. In Double Helix, for example, two motor-driven copper spirals twine gently within each other until the moment they touch and reverse the motor. The machines of Russian sculptor Eduard Bersudsky, by contrast, are better read as manifestations of the troubled artist's state of mind. Now living in Glasgow, where his works are shown as a theatrical installation called "Sharmanka" (Russian for hurdy-gurdy), Bersudsky began sculpting in Leningrad in the late 1960s. There, out of sight of the authorities, he poured his sarcasm and frustration at the Soviet Union's dead hand on artistic and cultural freedom into giant, busy works built of scrap iron and wooden carvings such as the precarious Pisa Tower — a collection of Jewish figures struggling frantically to keep their balance — or Noah's Ark, a warped bestiary sailing forever in search of dry land.

Perhaps the cleanest fusion of technology and artistic intent at the Phaeno — apart from the Zaha Hadiddesigned building itself, which is a triumph of experimental construction techniques and design aesthetics — is to be found in the 18 pieces brought by Arthur Ganson from his workshop at MIT in Boston. Ganson creates machines that are exquisitely engineered from low-tech materials to "express a feeling or a thought or a question." A wishbone hauling its own dream machine across the floor may not have a clear meaning, but that takes second place, he says, to "communicating the intensity and patience I put into getting the thing to walk." www.phaeno.de/mechanik.html