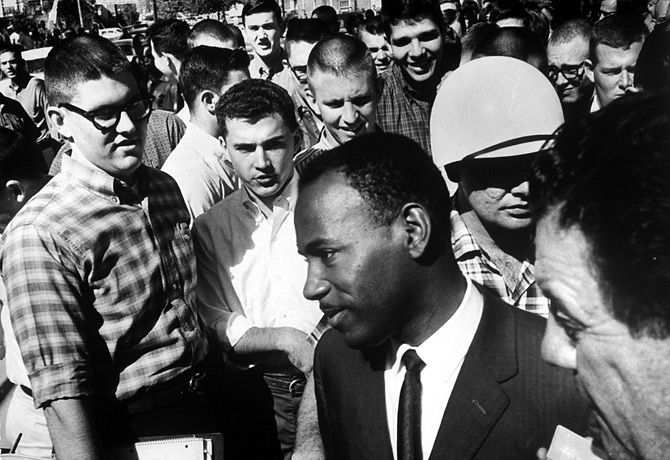

African-American student, James Meredith, is accompanied by two U.S. Marshals and surrounded by jeering white students after registering for entry at University of Mississippi on Sept. 1, 1962.

Historians have tended to believe that little more than political cynicism ever animated John Kennedy's response to civil rights—before and during his abbreviated presidency. As a rebellion among African Americans against Southern racism was mounting, J.F.K. saw the issue as less a moral crusade for the soul of America, as many white liberals believed it to be, than a potential barrier to his presidential nomination. He was mindful of the injustices of segregation but was more interested in making sure he secured white voters across the South. Kennedy's coolness toward the 1957 civil rights bill, the first major attempt to advance black equality since post-Civil War Reconstruction, provoked black civil rights leader Roy Wilkins to berate Kennedy publicly for "rubbing political elbows" with Southern segregationists.

But the Kennedys—John and his younger brother Robert, who served as J.F.K.'s Attorney General—have been given too little credit for progress on resolving America's oldest and greatest social divide. Even if J.F.K.'s passion for the cause came late, it made it possible for his successor, Lyndon Johnson, a white Texan, to become the architect of desegregation.

Although more a civil rights opportunist than a passionate convert to the cause, Kennedy sent repeated messages that if elected, he would use presidential power to promote equality for African Americans. He backed a strong civil rights plank in the Democratic Party's 1960 platform and refused to abandon that position when Southern Senators pressed him to do so. He argued that desegregation of public housing could be accomplished with one stroke of the pen as part of Executive action "on a bold and large scale." When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was unjustly jailed in Georgia, ostensibly for a minor traffic infraction but actually for trying to integrate a department store, Kennedy made a well-publicized call to King's wife offering to help arrange his release.

But once elected, Kennedy was reluctant to give in to demands for prompt and forceful action on civil rights. And his attention was elsewhere: he devoted his Inaugural Address almost exclusively to foreign affairs. Part of his restraint was simple political calculation: he and his brother knew any change would have to come from their branch, not Congress, which was dominated by conservative Southern Democrats serving as chairmen of key committees.