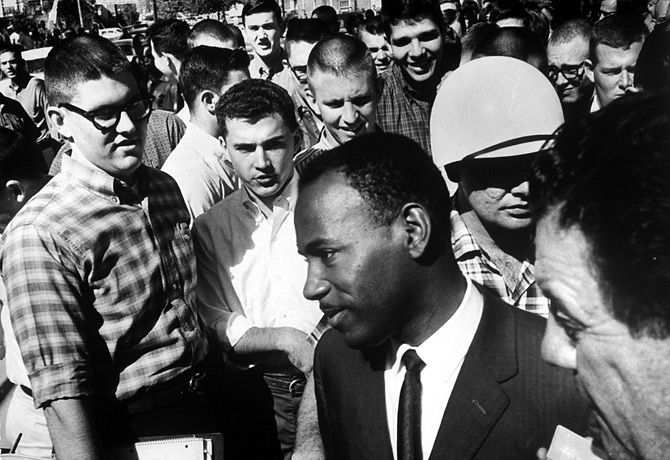

African-American student, James Meredith, is accompanied by two U.S. Marshals and surrounded by jeering white students after registering for entry at University of Mississippi on Sept. 1, 1962.

(2 of 3)

So Kennedy's actions were modest at first. To unify Congress and the nation behind an effective anticommunist foreign policy and win passage of other reform measures—a large tax cut to spur the economy, federal aid for education and health insurance for seniors—Kennedy confined his civil rights actions to setting up the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity in 1961. It was invented to eliminate discrimination in hiring federal employees and give federal contracts to businesses pledged to fair hiring practices. His caution allowed him to persuade Southern Senators to mute their opposition to the selection of Robert C. Weaver, a black expert on housing, as administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency. Kennedy also appointed Harris Wofford, a law professor and prominent liberal advocate of black equality, as a special presidential assistant for civil rights and told him it was time "to make substantial headway against... the nonsense of racial discrimination," although with "minimum civil rights legislation [and] maximum Executive action."

With such small steps, Kennedy won no applause from the country's civil rights advocates during the opening months of his presidency. "I'm convinced that he has the understanding and the political skill, but so far I'm afraid that the moral passion is missing," King said. When Kennedy wouldn't sign a controversial Executive Order desegregating federally financed housing, as he had promised, he received thousands of pens in the mail.

J.F.K.'s judicial appointments underscored his initial timidity on civil rights. Although he nominated Thurgood Marshall, a prominent figure at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a leading black advocate in Brown v. Board of Education, for appointment to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Kennedy also selected five Southern conservatives for federal judgeships, which reinforced the likelihood of continuing rulings on behalf of school segregation and black disenfranchisement across the South.

In 1962, when black and white activists met violent resistance to their antisegregation campaign in Albany, Ga., the President responded by endorsing Bobby Kennedy's rhetorical pleas for reasoned discussion by both sides. King reacted angrily by sending J.F.K. a telegram "asking for Federal action against anti-Negro terrorism in the South." Kennedy did federalize the Mississippi National Guard in September 1962 and made it possible to enroll James Meredith at the University of Mississippi, but his action came too late. By then, the bloodshed had left one Oxford, Miss., resident dead and 160 federal Marshals injured. A year later, in the spring of 1963, he hesitated to ask Congress to enact a comprehensive bill that would ban segregation in all places of public accommodation.