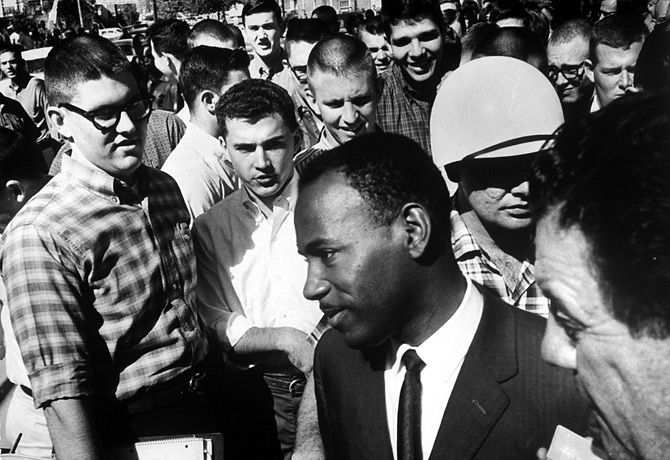

African-American student, James Meredith, is accompanied by two U.S. Marshals and surrounded by jeering white students after registering for entry at University of Mississippi on Sept. 1, 1962.

(3 of 3)

But a crisis in Birmingham, Ala., changed his mind about the imperative of civil rights, and thus was born Kennedy's real legacy on this front. In May, police and firemen attacked black demonstrators with snarling police dogs and high-pressure fire hoses that knocked marchers down and tore off their clothes. TV images of the police violence reached around the world and embarrassed the country. A picture on the front page of the New York Times and TV-news coverage of a dog lunging to bite a teenager on the stomach incensed Kennedy, who said the photo made him "sick."

Kennedy wanted to find a compromise that could end the crisis. King, who had been in a Birmingham jail since April, had already put renewed pressure on the White House by publishing a letter of complaint to white clergymen who were counseling patience and an end to civil disobedience. "I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion," King wrote, "that the Negro's greatest stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice... who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom."

Segregationists gave King even greater leverage in his demand for federal action when they bombed the home of King's brother and a Birmingham motel where King usually stayed. A riot in the city's black ghetto that left nine blocks of it a smoldering ruin raised fears of similar riots all over the South. Dealings with Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had publicly promised "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever," deepened Kennedy's sense of hopelessness about finding Southern moderates who would alter regional conditions without federal intervention.

The President now told his brother Bobby that the South will "never reform. The people in the South haven't done anything about integration for a hundred years, and when an outsider intervenes, they tell him to get out, they'll take care of it themselves, which they won't." The only solution Kennedy saw was a major federal civil rights statute that outlawed segregation in all places of public accommodation—parks, buses, swimming pools, theaters, hotels and restaurants. He believed such a law would give African Americans hope and remove the incentive to mob violence, not only across the South but also in ghettos all over the country.

In June, Kennedy gave a nationally televised address that was largely extemporaneous, since a formal speech had been handed to him only five minutes before he went on the air. A heartfelt appeal on behalf of a moral cause now trumped any self-serving political calculations. "We are confronted primarily with a moral issue," Kennedy said. "It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities... One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free... A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all." He followed his speech by asking Congress to enact a bill that removed race from consideration "in American life or law."

Although Kennedy's assassination five months later deprived him of the chance to sign the civil rights bill into law, he had finally done the right thing. That its passage in 1964 came under Johnson's Administration should not exclude Kennedy from the credit for a landmark measure that decisively improved American society forever. Although J.F.K. had been slow to rise to the challenge, he did ultimately meet it. That gives him a place in the pantheon of American Presidents who, in his own words, were profiles in courage.