(3 of 4)

Webster Groves has made a conscious decision to try to control the weather. The school would much rather prevent a disaster than clean up after one--which means that a child who so much as murmurs a threat toward himself or a teacher or another student is immediately under the microscope. But still the tempests come. "Drinking is the biggest problem," says police captain Doug Jacobs, class of '59, "and the parents that allow it." A child from a prominent family has a beer-and-booze party in the backyard while Mom and Dad are not home. There is the boy who dived into drugs and death threats and knives last year after his good friend died, the boy's soft, slashed wrist a souvenir of his journey through grief. He keeps in his planner the business cards of the hospitals that have treated him.

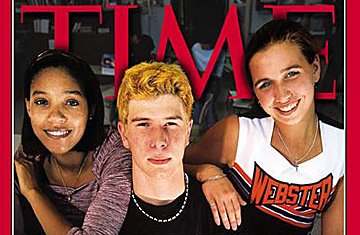

Teachers, like parents, have always faced the tension between roots and wings: how to keep kids safe and grounded; how to let them stretch and fly. But after so many shocking headlines, the adults are edgy and tempted to try to stamp out teenage rebellion and cruelty and popularity contests altogether. At a Webster pep rally, for the first time, individual team members are no longer introduced by name--to keep the cheering and booing from getting personal. Cheerleaders are picked by a panel of outside professionals, the football team rotates its captains so no one is favored, and anyone can show up for the Student Council meetings. Some students don't know who the senior-class president is. Adults "don't want to offend certain groups," says senior Lizzie Sprague, 17. "They are afraid [students] are going to go buy guns and kill everybody."

So if you aren't allowed to wear a hat, toot your horn, form a clique or pick on a freshman, all because everyone is worried that someone might snap, it's fair to ask: Are high schools preparing kids for the big ugly world outside those doors--or handicapping them once they get there? High school was once useful as a controlled environment, where it was safe to learn to handle rejection, competition, cruelty, charisma. Now that we've discovered how unsafe a school can be, it may have become so controlled that some lessons will just have to be learned elsewhere.

At times it seems that the faculty is engaged in a giant game of chicken--and some kids have learned to take advantage of it. For many, the extent of their forethought is making plans for the weekend, and even those are subject to change at the last minute. They get jobs, not necessarily to save for college but to buy a $400 leather jacket. So many kids skip their homework that most teachers stop assigning more than 15 minutes' worth: ask too much, push too hard, and the students will give up, drop out, become a menace to society. We have to strike a balance, the adults say. We have to be reasonable. We want them to enjoy themselves, have a certain freedom, before the world turns serious on them and there is no going back to 17.