(2 of 4)

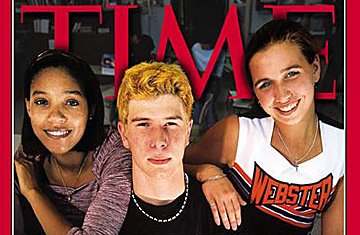

"This place" is Webster Groves High School, which sits off the main street of a pretty town of old elms and deep porches, about 10 miles southwest of St. Louis, Mo., where, when people ask you where you went to school, they are not referring to college. That's just the way it is here; high school tugs hard and holds on; people graduate and come back and send their kids, who graduate and do the same. This town of 23,000 is not as tony as nearby Clayton or Ladue; it has its mix of $90,000 cottages and $750,000 homes, young marrieds and old-line families and transient middle managers assigned to a stint in the St. Louis office who are looking for a comfortable place to settle and keep their kids on the track toward prosperity.

And yet this school, like every other school, is changing fast, by accident and design, because everything that touches it is changing too--the economy, family life, technology, race relations, values, expectations. TIME picked this school for the same reason marketing experts and sociologists like to wander this way when they are looking to take the country's temperature: the state of Missouri, especially the regions around St. Louis, are bellwether communities, not cutting edge, not lagging indicators, but the middle of the country, middle of the road, middle of the sky.

To study a school like this is to take an advanced course in compromise. Is it worth renouncing homework and offering credit for rock climbing if it keeps struggling kids in school and out of trouble, massages them through to graduation, maybe even a junior college? Is it worth letting kids work 30 hours a week after school, even if grades suffer and half a dozen are asleep in many a first-period class, in the belief that this is training for the "real world"? Is it worth busing 161 black kids in from St Louis, in a program that provides the school district where they go an extra $2 million in state aid, if parents and some teachers quietly argue that because of busing, overall achievement has fallen? Is it worth turning the principal and her deputies into sentries, equipped at all times not with books or rulers but with walkie-talkies, if it keeps the lid from blowing off?

After Columbine, West Paducah and Conyers, some schools have turned into citadels, metal detectors at the doors, mesh backpacks required. Not Webster. The doors are open at dawn and left unguarded; 96% of the kids polled this fall by the student newspaper say they feel safe in school. They say the kids get along pretty well, races mix, jocks and geeks hang out together. And yet they will say, if you ask, "Littleton could happen here." Last spring, after Columbine, someone scrawled a bomb threat on the wall of a boys' bathroom. The marginal kids know they are being watched, very, very closely.

If there is a secret to running a school in post-Columbine America, it is to make sure the place keeps no secrets from you. Since schools are populated by adolescents--that eager, suspicious, alienated, hyperbolic cohort--this alone is a full-time job. "There are two directions that schools are going in: to improve the climate and build trust, or to have metal detectors and transparent lockers," says assistant principal John Raimondo.