(7 of 8)

If a compromise is reached, the U.S. will have played a minimal role in it. The reason: anything that carries Washington's approval is now anathema in Iran. Some Administration advisers admit that open endorsement of Bakhtiar was a serious mistake, and that U.S. policy toward Iran should have remained noncommittal once the Shah's ruling days were clearly over. Particularly unfortunate was a statement by President Carter in January rebuking Khomeini and urging him to support the Bakhtiar government. State Department experts at that time were pretty well convinced that the Prime Minister had only the remotest chances of surviving.

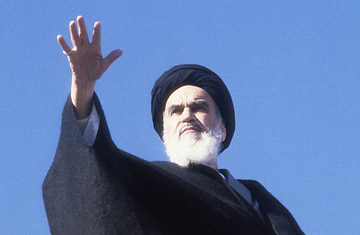

Belatedly changing a long-held policy of the U.S. embassy in Iran, Ambassador Sullivan has encouraged his subordinates to open a dialogue with the Khomeini forces. U.S. diplomats have initiated contacts with a number of the Ayatullah's key aides, both in France and Iran. By and large, they have been well received by Khomeini's representatives, who have stressed that it was not too late to repair relations between the Shilte leader and the U.S. Mehdi Bazargan, a Khomeini adviser in Tehran with broad political experience who is often mentioned as a potential government leader, emphasized to U.S. officials recently that a beneficial working relationship is "most definitely possible" with Washington. The crucial factor, he insists, is that any future trade relationship be based on an equitable exchange of goods and not distorted by extravagant sales of sophisticated weapons. At the same time, Khomeini's top economic adviser, Hassan Abdul Banisard, has implied that oil production will probably have to be cut in half to regulate the flow of capital into Iran.

Another valuable ally, in the U.S. view, would be Seyyed Mohammed Beheshti, a well-educated and widely traveled Ayatullah who has been Khomeini's chief behind-the-scenes contact in Tehran. But observers say it may take a while to see who the key figures around Khomeini prove to be; the Paris advisers may well give way to those who have supported him in Tehran.

Washington's greatest fear now is a military coup, which would inevitably spark a civil war and adversely affect any U.S. presence for many years to come. Says a State Department official recently returned from Tehran: "There is no question that a military takeover would be most dangerous for U.S. interests. It would blow away the moderates and invite the majority to unite behind a radical faction."