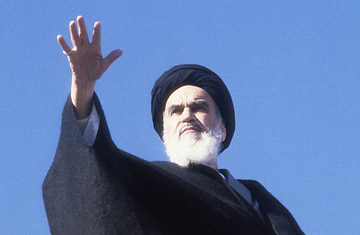

The chartered Air France 747 circled over the city and past the nearby Elburz Mountains three times before settling down gently on the tarmac of Tehran's Mehrabad Airport. As aides and reporters milled about, the frail old man, wearing a black turban and ankle-length robes, stepped out of the aircraft's door into the chill February morning. His back hunched, he clutched the arm of an Air France purser as he walked down the portable ramp to touch Iranian soil. After 15 years in exile, Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini. 78, spiritual leader of a revolution that has been building to a frightening climax, had come home at last. The moment was, conceivably, the start of a new era for a country that has seemed dangerously out of control.

After all the demonstrations of anger and mourning that have punctuated the year-long crisis, Iran went wild with joy. From all across the country, millions of people thronged into the capital; they lined the 20-mile route out to Behesht-Zahra Cemetery, where many of the martyrs of the revolution are buried, to catch a glimpse of the Ayatullah. "The holy one has come!" they shouted triumphantly. "He is the light of our lives!" So heavy was the crush of people that Khomeini had to be lifted from his motorcade and flown the last mile to the cemetery by helicopter. There, in Lot 17, he prayed and delivered a 30-minute funeral oration for the dead. "Is it human rights," he asked in a bitter if oblique reference to President Carter, "when we say we want to name a government and we get a cemetery full of people?" Then a boys' chorus sang: "May every drop of their blood turn to tulips and grow forever. Arise! Arise! Arise!"

From his bungalow at Neauphle-le-Chateau outside Paris, the Ayatullah had been sending home a steady stream of Elamiehs, messages summoning the faithful to bring down the monarchy in favor of what he has somewhat vaguely termed an Islamic republic. Much of the population heeded Khomeini. It was popular uprisings in his name that forced the hated Shah to take a vacation that might well extend to exile, and left the government in the uncertain hands of Prime Minister Shahpour Bakhtiar. Iron-willed, giving little hint of compromise, Khomeini has rejected the Bakhtiar government and damned it as illegal because it was appointed by the Shah.

But now on the scene, Khomeini faces far tougher tasks than rousing the people to fury against an unpopular autocrat. The Ayatullah has announced that he will set up a new revolutionary council for Iran. In so doing he risks a coup by an army whose generals, if not its soldiers, remain loyal to the Shah. He must pick up the numerous strands of opposition, united only in reverence for him and hatred of the monarch, and hold them together long enough to form a functioning government. It is a lot to expect from a spiritual leader wise in Koranic lore but woefully unskilled in Realpolitik. Perhaps aware of the huge risks involved, Khomeini after his return acted with uncharacteristic caution. Bakhtiar, for his part, kept the door open for negotiations with the Ayatullah, thereby raising hopes that a peaceful transition of power in Iran might still be possible.