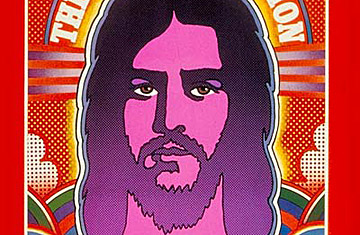

The Jesus Revolution

(4 of 11)

The movement is apart from, rather than against, established religion; converts often speak disparagingly of the blandness or hypocrisy of their former churches, but others work comfortably as a supplementary, revitalizing force of change from within. The movement, in fact, is one of considerable flexibility and vitality, drawing from three vigorous spiritual streams that, despite differences in dress, manner and theology, effectively reinforce one another.

THE JESUS PEOPLE, also known as Street Christians or Jesus Freaks, are the most visible; it is they who have blended the counterculture and conservative religion. Many trace their beginnings to the 1967 flower era in San Francisco, but there were almost simultaneous stirrings in other areas. Some, but by no means all, affect the hippie style; others have forsworn it as part of their new lives.

THE STRAIGHT PEOPLE, by far the largest group, are mainly active in interdenominational, evangelical campus and youth movements. Once merely an arm of evangelical Protestantism, they are now more ecumenical—a force almost independent of the churches that spawned them. Most of them are Middle America, campus types: neatly coiffed hair and Sears, Roebuck clothes styles.

THE CATHOLIC PENTECOSTALS, like the Jesus People, emerged unexpectedly and dramatically in 1967. Publicly austere but privately ecstatic in their devotion to the Holy Spirit, they remain loyal to the church but unsettle some in the hierarchy. In a sense they are following the lead of mainstream Protestant Neo-Pentecostals, who have been leading charismatic renewal movements in their own churches for a decade.

Together, all three movements may number in the hundreds of thousands nationally, conceivably many more, but any figure is a guess. The Catholic Pentecostals, often meeting in the privacy of members' homes, may number 10,000, but some observers believe that they could easily be three times that. Those converted by the straight evangelicals generally wind up on established church rolls, but are likely to be in the hundreds of thousands; the evangelistic staffs alone account for more than 5,000 people. The Jesus People—surely many thousands—are the most difficult to count. They often cluster in communes or, as they prefer to call them, "Christian houses"; the Rev. Edward Plowman, historian of the movement, estimates that there are 600 across the U.S. There is no doubt about their growth: Evangelist David Hoyt moved from San Francisco to Atlanta only a year ago and now has three communes and a cadre of 70 evangelizing disciples there, and centers in three other Southeastern cities. Much of the movement's main strength, however, has been built where it started, along the West Coast.

Some of the manifestations there could command places in William James' Varieties of Religious Experience. R.D. Cronquist, for instance, was a carpenter until last July, dabbling on the side in ministerial work. Now the mustachioed, goateed Cronquist is the pastor of the Grace Fellowship Chapel, a windowless, corrugated shed on