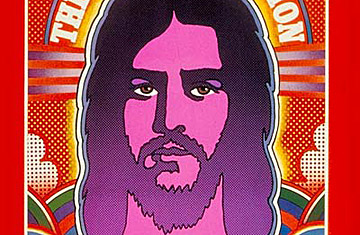

The Jesus Revolution

(2 of 11)

Some of the fascination for Jesus among the young may simply be belated hero worship of a fellow rebel, the first great martyr to the cause of peace and brotherhood. Not so, however, for the vast majority in the Jesus movement. If any one mark clearly identifies them it is their total belief in an awesome, supernatural Jesus Christ, not just a marvelous man who lived 2,000 years ago but a living God who is both Saviour and Judge, the ruler of their destinies. Their lives revolve around the necessity for an intense personal relationship with that Jesus, and the belief that such a relationship should condition every human life. They act as if divine intervention guides their every movement and can be counted on to solve every problem. Many of them have had serious personal difficulties before their conversions; a good portion of the movement is really a May-December marriage of conservative religion and the rebellious counterculture, and many of the converts have come to Christ from the fraudulent promises of drugs. Now they subscribe strictly to the Ten Commandments, rather than to the situation ethics of the "new morality"—although, like St. Paul, they are often tolerant of old failings among new converts.

The Jesus revolution rejects not only the material values of conventional America but the prevailing wisdom of American theology. Success often means an impersonal and despiritualized life that increasingly finds release in sexploration, status, alcohol and conspicuous consumption. Christianity — or at least the brand of it preached in prestige seminaries, pulpits and church offices over recent decades — has emphasized an immanent God of nature and social movement, not the new movement's transcendental, personal God who comes to earth in the person of Jesus, in the lives of individuals, in miracles (see box, page 60). The Jesus revolution, in short, is one that denies the virtues of the Secular City and heaps scorn on the message that God was ever dead. Why?'

But why not? This is the generation that has burned out many of its lights and lives before it is old enough to vote. "The first thing I realized was how different it is to go to high school today," wrote Maureen Orth in a "Last Supplement" to the Whole Earth Catalog. "Acid trips in the seventh grade, sex in the eighth, the Viet Nam War a daily serial on TV since you were nine, parents and school worse than 'irrelevant'—meaningless. No wonder Jesus is making a great comeback." The death of authority brought the curse of uncertainty. As Thomas Farber writes in Tales for the Son of My Unborn Child: "The freedom from work, from restraint, from accountability, wondrous in its inception, became banal and counterfeit. Without rules there was no way