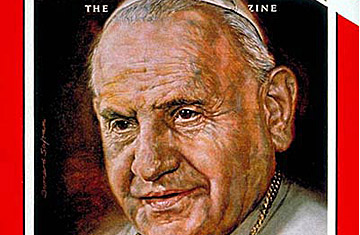

Pope John XXIII

(7 of 7)

The good life, however, often muffles the hard impact of the Christian message, and church leaders complain that Christians frequently make their churches into something resembling comfortable and conformist country clubs. Says Dr. Jaroslav Pelikan of Yale Divinity School: "They're busy, busy, busy with church activities in which you don't even hear about God." Christianity is also menaced, believes the World Council of Churches' Willem Visser 't Hooft, by syncretism: a general religiosity that mixes all religions —Islam, Judaism, Hinduism—"into an unholy Irish stew. If one believes in revelations through Christ, it is impossible to become part of a religious cocktail where the ingredients get lost."

For all his prosperity and technical progress, modern man is absorbed more and more in a society that makes less and less sense to him. Frequently, his life has no meaning, no sense of direction or fulfillment. Yet the Christian Church often addresses itself to a vague "peace of mind," failing to understand the tension and anxiety of a changing world and the need to say something cogent about them. "Without the aid of religion, the world is like the prodigal son going off and getting more and more weary and miserable," says English Jesuit Martin D'Arcy. "I believe man is in extremity. There is loneliness and death everywhere, and here is this life-giving philosophy which we must bring to them."

That challenge sums up the duty of the Christian faith to forget the quarrels of the past and work at presenting the ancient Christian message of redemption in a clearer and more modern light. No one believes that the Christian churches will join together in this century. But Pope John's actions have begun a reconciliation that is bound to make the Christian message a more unified and vital force. It is already obvious in the unusual sight of Protestant pastors and Catholic priests exchanging pulpits in Holland, of Catholic priests at the consecration of Episcopal bishops in Dallas and Boston, of a gathering of 150 priests and ministers in St. Louis to discuss reform and reunion. It was most dramatically illustrated by the honored places held at the Ecumenical Council by non-Catholic observers who only recently were regarded by their hosts as heretics and schismatics.

Always an Optimist. To a Christianity deeply bothered by the world's condition, Pope John XXIII has brought something more than a simple feeling of good will: a renewed sense of the optimism at the heart of the Christian message. "We are much too pessimistic and not joyful enough," complains Swiss Theologian Karl Barth, who calls for a "theology of freedom that looks ahead and strives forward" to suit "the nearly apocalyptic seriousness of our time." Says Pope John: "Men have come and gone, but I always remained an optimist, because that is my nature, even when I hear near me deep concern over the fate of mankind."

To the world at large, John has given what neither science nor diplomacy can provide: a sense of its unity as the human family. That sense is at the core of the Christian tradition, whose God lives in history and invites the family of man to help him form it. If the invitation goes begging in a world besieged by tension and seduced by its own accomplishments, Christianity must share the blame. Pope John believes that man should be saved where he is, not where he ought to be. By bringing Christianity to a new confrontation with the world and salving the wounds that have torn it for centuries, the Pope has helped vastly to recapture the Christian sense of family.

For, in a time of apocalyptic seriousness, man has realized more than ever that he does not live by bread alone.

Nor by guns.

* '— Others: Islam, 430 million; Hinduism. 335 million; Confucianism, 300 million; Buddhism, 153 million.

* Theologically, tradition is the body of doctrine attributed to Christ or his Apostles but handed down orally rather than as Biblical revelation.