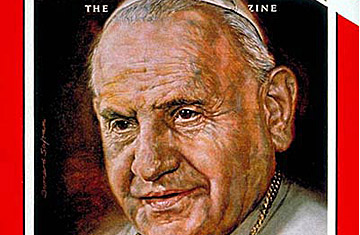

Pope John XXIII

(5 of 7)

Host to Rulers. In the papacy. John asked to be known not as a diplomatic, political or learned Pope, but as "the good shepherd defending truth and goodness." He sallied out of the Vatican to orphanages, jails, schools, churches—139 times. He dispensed with such customs as that of barring visitors from St. Peter's dome while the Pope is walking in the garden below. Said John: "Why shouldn't they look? I'm not doing anything scandalous." He pronounced himself embarrassed at being addressed as "Holiness" or "Holy Father.'' and admitted that he could not get used to thinking of himself in the plural. "Don't interrupt me—I mean us!" he once joked. He even granted a papal audience to a traveling circus, and fondly patted a lion cub named Dolly. "You must behave here," ordered John. "We are used only to the calm lion of St. Mark."

John welcomed more rulers (32) than any other Pope, and received some historic papal guests: the first Greek Orthodox sovereign to visit the Pope since the days of the last Byzantine emperor, the first Archbishop of Canterbury since the 14th century, the first chief prelate of the U.S. Episcopal Church, the first Moderator of the Scottish Kirk, the first Shinto high priest. When Jacqueline Kennedy came to visit, John asked his secretary how to address her. Replied the secretary: ' 'Mrs. Kennedy,' or just 'Madame.' since she is of French origin and has lived in France." Waiting in his private library, the Pope mumbled: "Mrs. Kennedy, Madame; Madame, Mrs. Kennedy." Then the doors opened on the U.S. First Lady and he stood up, extended his arms and cried: "Jacqueline!"

The Pope's frequent pleas for peace are more sympathetic and convincing than those of any of his predecessors as he has urged nations to "hear the anguished cry which from every part of the earth, from the young innocents to the old. rises toward heaven: 'Peace! Peace!'" Even Nikita Khrushchev was moved. He praised the Pope's pleas for peace, sent him a greeting on his 80th birthday. Many in the Vatican thought the Pope should ignore it, but John sat down and wrote a reply: "Thank you for the thought. And I will pray for the people of Russia."

CHRISTIANITY: "AN IRRELEVANCY"?

Pope John's view of today's world owes little to the long-cherished Augustinian conception of it as divided into the City of God and the City of Man. To John, the church is not an exclusive club with its own narrow rules but a mother who must follow man into the mud as well as the sky. "It is the church that must bring Christ to the world," he said in a recent radio message. That is a never-ending task, to be attempted at a time when the world presents far more formidable obstacles to Christianity than the paganism of the Greeks and Romans ever did.

The great majority of Protestant and Catholic clergymen and theologians—as well as many non-Christians—agree that Christianity is much stronger today than it was when World War II ended. Their reason is not the postwar "religious revival" (which many of them distrust as superficial) or the numerical strength of Christianity. It is that the Christian Church has finally recognized and faced the problems that have cut off much of its communication with the modern world.

Says Notre Dame's President Theodore Hesburgh: "We better understand the job that is before us. The challenge is to make religion relevant to real life."

Melting Together. Christianity can justly claim to have relevance to impart. It offers a unified view of the world that has attracted men for centuries, and answers questions of love, life and death as few other religions do. Says Theologian Vorgrimler: "Real religion requires that God come close to man—and there Christianity has the most radical answers, by teaching that God has become man himself. This is a melting together of God and the world." German Marxist Philosopher Ernst Bloch admits: "Christianity is still a light shining in the darkness, and the light is stronger now."

Yet many Christians believe, with Catholic University's Monsignor John Tracy Ellis, that in practice "religion is just an irrelevancy in the lives of many people—the great majority." Gloomy Christian theologians are fond of speaking of a post-Christian age—the Christian Church estranged from modern society. "We need a theology of the 20th, or even the 21st century," says Dominican Dominique Dubarle, professor at the Institut Catholique de Paris.

Modern man's world offers alluring alternatives to the Christian way of life. He is captivated by his own technical and scientific accomplishments, devoted to the enjoyment of his plentiful goods, self-sufficiently distrustful of the supernatural. "The greatest enemy of Christianity," says Philosopher Mortimer Adler, "is man's self-confidence. The more power he has, the less religious he becomes." Much of that power has been given to him by science, which has made its launching pads and atomic reactors the age's equivalent of medieval cathedrals.

Theology of Space. Christian theologians insist that there is no basic conflict between religion and science—and a lot of scientists agree. They are convinced that if the Christian faith managed to assimilate Darwin there are few other scientific discoveries it cannot handle. Science's function is to describe the nature and phenomena of life—and leave the description of its purpose to religion. Says the University of California's Nobel-prizewinning Chemist Willard Libby: "Science and religion are not in conflict, nor are they in full cooperation. They are fulfilling very different needs."

In conflict or not, science is clearly something that the Christian faith must deal with more knowingly. While vastly expanding man's horizons, science has lowered man on the scale of existence and tacitly called into question the Christian teaching of his unique relationship with God. "Scientific history," says Oxford's Regius Professor of Modern History Hugh Trevor-Roper, "has succeeded in removing man from the center of the universe."