(5 of 7)

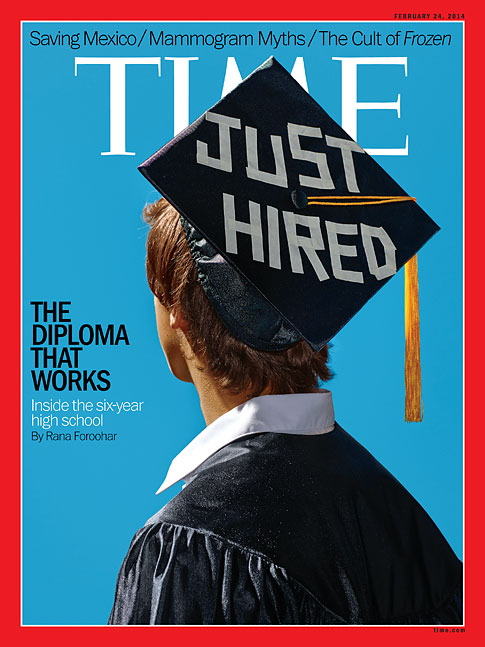

Many of IBM's unfilled positions are in the middle-skilled area--jobs that require less than a four-year degree but more than a high school diploma. This underscores an interesting truth about the American economy: despite all the press about the middle class shrinking, middle-income jobs are actually forecast to grow. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics figures, middle-skilled jobs with a technology bent--which include positions like entry-level software engineers, medical technicians and high-tech-manufacturing workers--will increase by 17.5% from 2010 to 2020, just as fast as high-skilled jobs and far faster than lower-end ones. But while we have plenty of Ph.D.s and burger flippers, we don't have enough people with skills in between. Too many four-year graduates are overeducated in the wrong areas: liberal-arts students graduating today are at a major salary disadvantage compared with peers in the sciences, and a full 27% of people with postsecondary certificates make more than the average bachelor's-degree recipient.

The trick is boosting those credentials--and the two-year-college graduation rate of 10%. In seeking to narrow the divide between high school and community college, the P-Tech blueprint represents the culmination of 30 years of secondary and postsecondary school reform in America. It has a strong academic core. It picks up certain elements of the "career academy" model, which creates high schools with links to particular industries, like finance or telecommunications, and adds a dash of the "early college high school" model, where small, specialized schools in deprived socioeconomic areas allow kids to complete some college credits in high school, reducing the cost of a degree later and improving their chances of graduating. It throws in corporate help in curriculum development and mentoring to ensure employable workers.

But P-Tech adds a final, crucial twist, that job guarantee for graduates. "The P-Tech model takes the best of these other ideas and then goes a step further by bridging the jobs divide," says Harvard education professor Robert Schwartz, author of the seminal 2011 Pathways to Prosperity report on career training and school reform, who lauds the model. "I give IBM a lot of credit for that."

In many ways, P-Tech is a white collar, modernized version of the successful Germanic model in which students are taught curriculums geared toward specific, career-oriented skill sets. (Countries that follow this model, including Germany, Austria, Switzerland and the Scandinavian nations, have lower-than-average rates of youth unemployment.) In other ways, it's more creative and focused on basic intellect building, which is important since it's impossible to fully predict what the jobs of the future will require.