(2 of 7)

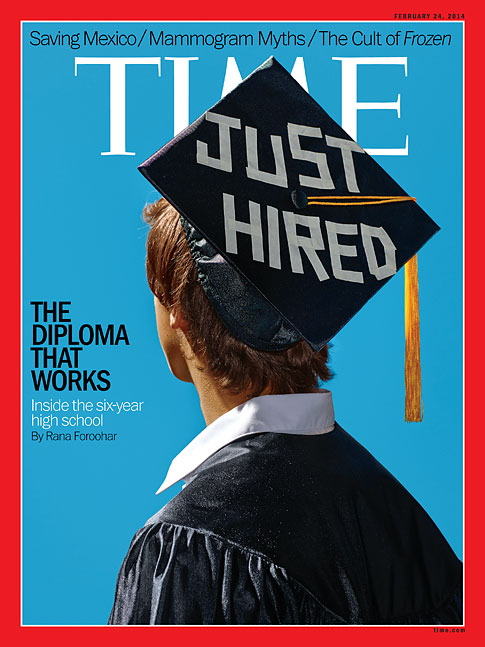

Many U.S. leaders--including Obama, Education Secretary Arne Duncan, scores of blue-chip CEOs and executives and a sizable number of top educators--believe we're once again at such a turning point. And many of these leaders are pushing the idea that when it comes to the length of secondary education, six should be the new four. In Tennessee, Republican governor Bill Haslam used his Feb. 3 State of the State address to unveil a proposal that would provide two free years of community college for any high school graduate. Oregon lawmakers are studying a similar proposal. The obstacles are considerable, starting with the most obvious: Who pays? Pilot programs are one thing, but taking the six-year high school mainstream will require a substantial commitment in funding--and faith that the economic benefits of a better-educated workforce will offset the costs.

Evidence suggests that expanding education beyond 12th grade can be powerful. A four-year high school degree these days guarantees only a $15-an-hour future, if that. According to projections by the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University, the U.S. economy will have created some 47 million job openings in the decade ending 2018, and nearly two-thirds of them will require some postsecondary education. The Center projects that just 36% of American jobs will be filled by people with only a four-year high school degree--half of what that number was in the 1970s. On average, workers with an associate's degree will earn 73% more than those with only a high school diploma.

But realigning American education for the jobs of the future isn't just about the duration of school. It's a question of what to study and how to encourage kids to see their education through. And that's why programs like Sarah E. Goode--an approach known as Pathways in Technology Early College High School, or P-Tech for short--are attracting so much attention. The P-Tech model was originally developed by IBM, the New York City department of education and the City University of New York. Two and a half years in, the Brooklyn school that pioneered the approach has been visited by everyone from the President and Harvard academics to Chinese officials. Its first class will graduate in 2018, though many will complete all the requirements before then. Right now about half of the juniors--none of whom were screened for ability and many of whom will be the first in their family to graduate from high school--are already taking college-level math. It's an impressive achievement in a city where only 64.7% of kids graduate from high school. Rashid Davis, the principal there, says the public-private partnership is invaluable: "It's incredible how much further children can reach when industry is closer to them to help set the context for learning."

LEARNING TO EARN