Growing up in Brooklyn's working-class Bay Ridge neighborhood in the 1950s, Janet Yellen learned a lot about the human side of economics. "My father was a family doctor, and both he and my mother lived through the Depression," she says. "I heard a lot of stories about it." She also saw the Brooklyn dockworkers and factory laborers come in and out of her father's home office, paying $2 cash to be seen, or not paying, depending on how things were going. "I came to understand the effect that unemployment could have on people in human terms."

Five decades later, as head of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, Yellen would raise concerns about a fledgling bubble in subprime mortgages that would balloon into the worst economic disruption since the Great Depression--the first of the Fed's 19 policymakers to do so. And in 2010, as the Fed's vice chair, Yellen would find herself helping devise the latter stages of a controversial plan to buy trillions of dollars in assets, shoring up the battered economy. For millions of workers in the U.S. economy, that plan--the Fed's so-called quantitative easing--may well have been the difference between losing a job and keeping it, between searching in vain and finding an opportunity.

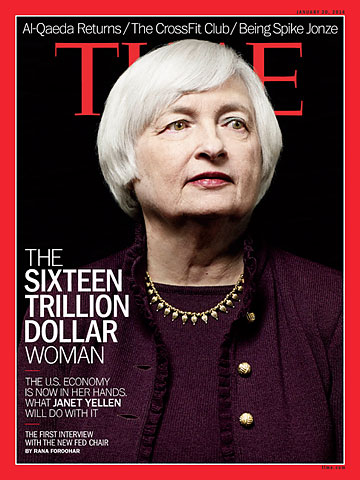

On Jan. 6, Janet Louise Yellen was confirmed by the Senate as the 15th chair of the Federal Reserve System of the United States. As Fed chair, she is responsible for deciding where and how money flows, not just in the U.S. but also in much of the world, given the dollar's position as the global reserve currency. She is the first woman to hold the job. More important, she is also the first chair who is an openly reform-minded Keynesian--meaning she lives by the belief that monetary policy can temper the swings of the business cycle, strengthening the economy for workers as well as financiers. The diminutive 67-year-old Yellen smiles often and comes across as something like your favorite aunt, if your aunt had a chair with her own brass nameplate in the middle of the 22-ft.-long Fed Board of Governors conference table. When she's not charting the economic course of the free world, Yellen is a foodie who likes to travel with her Nobel Prize--winning husband, stopping at any Michelin-starred restaurants they encounter along the way.

In the coming months and years, she may need to work hard to keep her smile. Yellen, a 36-year veteran of the Fed, embarks on her new job at a precarious moment. Unemployment is receding, and the recovery is building, but the Fed must now unwind the unprecedented quantitative-easing program. Taper off the $75 billion-a-month purchase of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed assets too quickly, and the recovery could stall. But wean the economy too slowly, and the risks of asset bubbles and longer-term inflation, which critics like eminent Fed historian Allan Meltzer believe are already a huge issue, could increase further--with consequences that nobody can really predict since there's no road map for where we are now and no precedent for the policy decisions of the past few years.