(5 of 8)

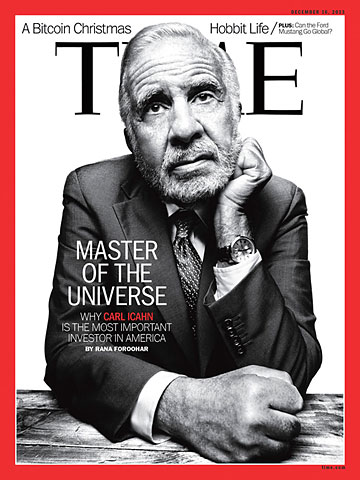

Icahn defends his recent targeting of companies from Apple to Netflix to Motorola and says he plans to push not only for more buybacks but also for more board seats with target companies. Sometimes it doesn't require a push. Three companies--Transocean, Talisman Energy and Nuance Communications--have recently invited Icahn to add directors to their board, perhaps thinking, as Icahn likes to say, that "peace is better than war."

"Many businesses in this country are terribly run," Icahn says. "While there are a number of good board members, you've got some board members making $400,000 a year that are actually counterproductive. They're not going to go against their buddy [the CEO] who put them there." Icahn believes his role as an activist is to shake up boards, improve governance and make corporate America accountable. Indeed, he believes that it is the cure for what ails America, both economically and socially. He blames "poor corporate governance for a growing disparity in income and slow growth" in the U.S. "If we don't get better corporate governance, we're going to lose our hegemony."

Growing Up Icahn

In many ways, Icahn's success is testimony to the U.S.'s unique place in the world. "I couldn't have done what I do in any other country," he says, referring to the path of a working-class kid from Queens to Princeton, then to Wall Street and a penthouse duplex at 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue, in which he and his second wife and former assistant Gail Golden live amid corporate-raider chic--all marble and red-and-gold curtains, with the requisite Impressionist paintings and a power view of the GE building. This is where Icahn does much of his wheeling and dealing as a maid stands by with double martinis and a private chef serves salmon canapés and a slightly better version of the sort of dinner you'd find nearby at the St. Regis.

"My dining room is the best place to have dinner in the city," he says, recounting deals that were cut there, from the revamping of health-food firm Hain Celestial (whose stock price has quadrupled since Icahn took over) to the splitting of Motorola (which made him nearly $1 billion). "It's quiet, and you can really talk."

And we do. While Icahn is a terror if you are on the wrong side of a deal with him, he can be a pleasure over cocktails, a natural-born storyteller with a disarming tendency not to take himself too seriously. (No rich guy turned philosopher, à la Soros or Ray Dalio, is he.) He tells me about his tough childhood in Queens, with his cantor father and schoolteacher mother, who were both boastful (to friends) and critical (to him) of their unusually bright only son. Icahn says his father, who "never spent a dime," promised to pay his way into the Ivy League, but when he was accepted at Princeton, his dad balked at paying his room and board. "I said, 'How am I going to eat?' and they said, 'That's your problem.'"

So Icahn took a job as a cabana boy at a Long Island beach club and learned to play cards with patrons to win his college money. "I get three books on poker, and in one week I read them, all these books with numbers," says Icahn, who is notoriously good at math. "Pretty soon, I know poker 10 times better than the best of them."