(2 of 8)

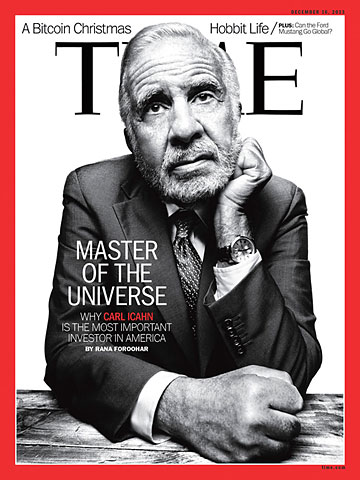

Icahn's move on apple comes near the end of a particularly successful year in which he has forced a change of direction at a number of other firms, including Chesapeake Energy and Herbalife, and just this month placed allies on the board of Talisman Energy, a Canadian oil and gas company. In a year when the Dow Jones industrial average is up 21%, Icahn's firm is up 201.5%.

Nor is Icahn alone. He is part of an increasingly powerful wave of opinionated investors who call themselves shareholder activists--a clever rebranding for some of them, who used to be known as corporate raiders. In addition to Icahn, who was around the first time, today's prominent activists include people like Bill Ackman, Daniel Loeb, David Einhorn, Ralph Whitworth and several others. They all have different styles and somewhat different methods. But the common thread is that they are taking on some of America's most high-profile firms. In the past year or two alone, these activists have targeted companies including Dell, JCPenney, Herbalife and Hewlett-Packard.

The last time these corporate dramas played out so vividly was the Roaring '80s. Everything was big then: balance sheets, shoulder pads, hair, egos. And the stock market seemed unstoppable until Black Monday delivered a comeuppance on Oct. 19, 1987, when the Dow plummeted 22%. The corporate raiders came to be known as "barbarians at the gate," after the title of a book by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar chronicling the leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco in 1988. That was a megadeal done with megadebt--the sort that came to epitomize the era.

Icahn was a major figure in that "Greed is good" scene, embarking on hostile takeovers of firms like aging airline TWA (whose assets he sold off piecemeal to pay for the deal) and demanding asset sales at Texaco, where he owned a major stake (he pushed for billions' worth of dividend payments and share buybacks).

While a lot of it was simply about making money--which Icahn freely admits is his major motivation in life--the barbarians of the '80s were inadvertently telling us something important about the excesses within corporate America and the economy as a whole. Shifts in SEC rules had allowed dealmaking to take precedence over investing. Throughout the '80s and the decades that followed, share buybacks proliferated, and corporate investments into research and development suffered.

Few in corporate America seemed to question these shifts. Sure, companies might be bought and sold and people would lose their jobs, but wasn't that all part of capitalism's creative power? Debt, in this context, wasn't always considered a bad thing--if companies weren't using cash and assets productively, why not lever up and give money back to investors? The tax code, which increasingly came to favor debt over equity thanks to the efforts of the financial lobby, only made such tactics more tantalizing.