(3 of 7)

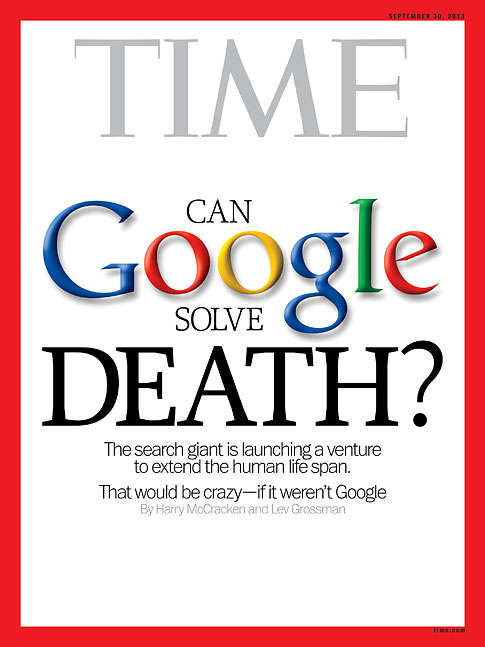

Google has never tried to solve anything quite as far afield as, well, mortality. The idea of treating aging as a disease rather than a mere fact of life is an old one--at least as a fantasy. And as a science? The American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine has been around since 1992, but the discipline it represents has yet to gain much of a foothold in mainstream medicine. Research has been slow to generate results. Consider Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, a Cambridge, Mass., company built around a promising drug called SRT501, a proprietary form of resveratrol, the substance found in red wine and once believed to have anti-aging properties. In 2008, GlaxoSmithKline snapped up Sirtris for $720 million. By 2010, with no marketable drug in sight and challenges to existing resveratrol research, GlaxoSmithKline shut down trials. Other anti-aging initiatives exist purely as nonprofits with no immediate plans for commercial products.

Why would Google be able to get traction on aging when huge pharmaceutical companies haven't? Page himself doesn't oversell his knowledge of the industry. "I don't have as much personal expertise in the technology," he admits. "I have some knowledge of it, just being in Silicon Valley." Google has invested in gene-sequencing company 23andMe, a startup co-founded by Anne Wojcicki, Brin's wife. And in February, Levinson and Brin joined Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner in organizing the $33 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, to "recognize excellence in research aimed at curing intractable diseases and extending human life."

It's a lot easier to take Google's venture seriously if you live under the invisible dome over Silicon Valley, home to a worldview whereby, broadly speaking, there is no problem that can't be addressed by the application of liberal amounts of technology and everything is solvable if you reduce it to data and then throw enough processing power at it.

The twist is that the technophiles are right, at least up to a point. Medicine is well on its way to becoming an information science: doctors and researchers are now able to harvest and mine massive quantities of data from patients. And Google is very, very good with large data sets. While the company is holding its cards about Calico close to the vest, expect it to use its core data-handling skills to shed new light on familiar age-related maladies. Sources close to the project suggest it will start small and focus entirely on researching new technologies. When will that lead to something Google might actually sell? It's anybody's guess.

What's certain is that looking at medical problems through the lens of data and statistics, rather than simply attempting to bring drugs to market, can produce startlingly counterintuitive opinions. "Are people really focused on the right things?" Page muses. "One of the things I thought was amazing is that if you solve cancer, you'd add about three years to people's average life expectancy. We think of solving cancer as this huge thing that'll totally change the world. But when you really take a step back and look at it, yeah, there are many, many tragic cases of cancer, and it's very, very sad, but in the aggregate, it's not as big an advance as you might think." Page, in other words, is a man for whom solving--not curing--cancer may not be a big enough task.