(2 of 7)

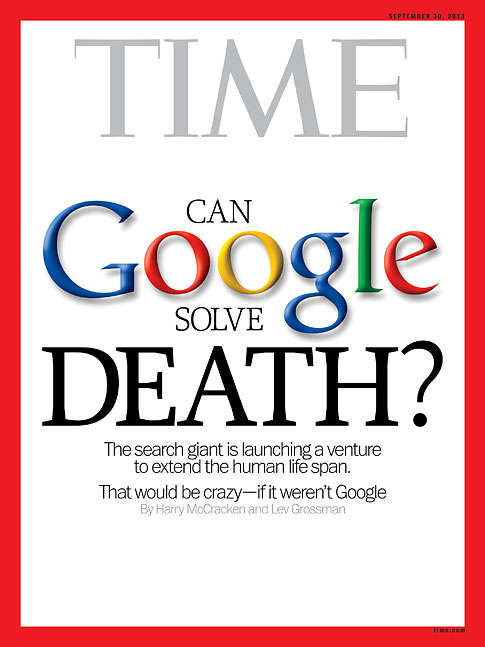

It's worth pointing out that there is no other company in Silicon Valley that could plausibly make such an announcement. Smaller outfits don't have the money; larger ones don't have the bones. Apple may have set the standard for surprise unveilings, but excepting a major new product every few years, these mostly qualify as short term. Google's modus operandi, in comparison, is gonzo airdrops into deep "Wait, really?" territory. Last week Apple announced a new iPhone; what did you do this week, Google? Oh, we founded a company that might one day defeat death itself.

The unavoidable question this raises is why a company built on finding information and serving ads next to it is spending untold amounts on a project that flies in the face of the basic fact of the human condition, the existential certainty of aging and death. To which the unavoidable answer is another question: Who the hell else is going to do it?

New Horizon

Google's fondness for moon shots, and its ability to take them, can be attributed in large part to Page himself. When he was a Stanford computer-science grad student, his insight that the most relevant Web pages are those with the most links to them became the basis of a remarkably precise search engine, which he created with fellow student Sergey Brin. Google became a company in 1998 and a phenomenon shortly thereafter. Page served as its chief executive until 2001, when tech veteran Eric Schmidt was brought in from software giant Novell. Even then, the unconventional troika of Page, Brin and Schmidt raised eyebrows, but the power sharing led to Google's monster growth years. In April 2011, Page reclaimed the CEO title, and Schmidt became executive chairman.

The effect of Page's leadership at Google was immediately clear. In 2012 the company closed a massive $12.5 billion acquisition of troubled handset maker Motorola Mobility in a bid to begin manufacturing its own hardware. Page also reshaped Google's management structure, creating the so-called L Team (L for Larry) of top managers. There were notable departures, including employee No. 20, Marissa Mayer, who left to run Yahoo. Most important, Page has shown that Google, long criticized as a one-trick pony dependent on serving ads, can grow its other businesses. Most of its $50 billion in revenue still comes from search-related ads. Analysts estimate that YouTube is a $4 billion business, and Android, its mobile operating system, is estimated to bring in an additional $6.8 billion from use on smartphones.

Beyond all that is the simple fact that Page is uncommonly ambitious and impatient, and he wants the company he created to be as well. "For me, it was always unsatisfying if you look at companies that get very big and they're just doing one thing," says Page. "Ideally, if you have more people and more resources, you can get more things solved. We've kind of always had that philosophy." Longtime Google observers tend to agree. "Guys like Larry don't focus on preserving value; they just work on building new value," says Ben Horowitz, co-founder of venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. "It's the advantage of having made something from nothing."