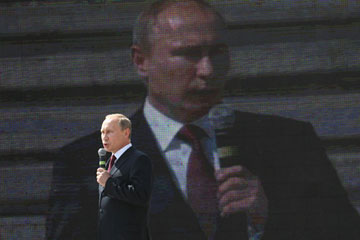

Russian President Vladimir Putin delivers a speech at the opening of the Barmaley Fountain on August 23, 2013 in Volgograd, Russia.

(5 of 7)

Prokhanov's anti-Americanism has recently made its way into the political mainstream. This winter, when Russia banned U.S. families from adopting Russian children, the Kremlin official in charge of child welfare, Pavel Astakhov, described American adoptive parents as buyers in the orphan trade and closet pedophiles. He even suggested in an interview with me that the U.S. is trying to depopulate and conquer Russia's resource-rich regions by adopting all their children.

On Russian state TV, Uncle Sam has been turned into a bogeyman for all occasions, blamed for everything from slowing economic growth--expected to be 1.8% this year, compared with an average of 7% during Putin's first two terms as President--to the dumbing down of Russian youth. When a wave of street protests broke out against Putin in late 2011, he called the organizers paid "agents" of the West. The American development agency USAID was then accused of fomenting the protests and summarily kicked out of Russia in September 2012.

None of this has stopped the growing discontent over corruption, inflation and abject social services, but it has served as a useful distraction. "It is a handy trick," says Alexander Konovalov, an expert on U.S.-Russian relations at the Foreign Ministry's diplomatic academy. "When a typical Russian wonders why he has no pension, the state can either give him some complicated answer or it can say, 'Comrade! What pension? The enemy is at the gates!'" This message works. In a survey released in June by the Levada-Center, an independent Russian pollster, a third of respondents saw the U.S. as Russia's main geopolitical foe. In a 2012 Levada poll, 76% said the U.S. is "an aggressor that aims to control all the countries of the world."

And such views are not confined to aging cold warriors. Maria Baronova was born in Moscow during the twilight of the Soviet Union and takes her social cues from the hipsters of Brooklyn. A feminist single mother, libertarian and political activist, she is opposed to Putin on almost every issue. Most weekdays, she puts on a stylish dress and goes to court, where she is on trial for organizing a demonstration against Putin that turned violent last year. The charges against her--"inciting mass unrest"--carry a sentence of up to two years. But get her talking about American foreign policy and Baronova, 29, can sound like an R-rated version of Putin. Her generation, though Western in its tastes, grew up on the humiliations of the late 1990s, as when they watched live footage of NATO warplanes bombing Russia's ally Yugoslavia into submission. "We all became rabid anti-Westerners after that," she says.

It was not much easier for her to watch the U.S.-backed revolution in Serbia, which ousted President Slobodan Milosevic in 2000, weakening a cultural connection that had stood for centuries on Slavic unity and the Orthodox Christian faith. That was the first of the Color Revolutions, the popular uprisings that brought pro-Western leaders to power across the former Soviet Union, usually with U.S. support. Three years after Serbia there was the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2003, then the orange one in Ukraine in 2004 and the tulip one in Kyrgyzstan in 2005. These perceived intrusions by Washington infuriated Putin, who called them U.S. exercises in "political engineering in regions that are traditionally important for us."