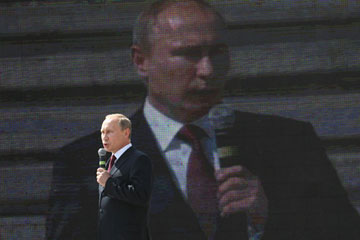

Russian President Vladimir Putin delivers a speech at the opening of the Barmaley Fountain on August 23, 2013 in Volgograd, Russia.

When Vladimir Putin emerged from his black limousine in Volgograd's train-station square on Aug. 23, squinting and blinking to adjust his eyes to the blazing sun of the steppes, he found an odd mix of people before him. Scattered among the few hundred elderly veterans who had gathered to greet him were a dozen leather-clad members of the Night Wolves, a Slavic motorcycle gang, standing at attention. But it was Putin's kind of crowd. Diving in, he returned the bikers' bear hugs and let the veterans get close enough to take selfies with him on their cameras, even as a secret-service agent stood two steps away with a black briefcase containing Russia's nuclear launch codes--Putin's nuclear football. "He's a colossal historical figure," remarked Mikhail Sidorov, a veteran of World War II, who stood watching at the edge of the crowd. "He's not quite Stalin yet, but he's getting there."

This was meant to be a compliment, and Putin might well have taken it as one. Throughout the weekend of jingoism that Putin had come to inaugurate, Joseph Stalin was cast not as the despot who killed millions of his fellow citizens but as a founding father who transformed Russia from an agrarian society into an industrial giant capable of beating back the Nazi invasion. Later that day, Stalin's face was projected in green laser lights over a rally on the grounds of a former tank factory. A quarter-million people from around the Slavic world had gathered in Volgograd for the rally commemorating the start, 71 years earlier, of the Battle of Stalingrad, as the city was known during Stalin's rule. At the rally's culminating moment, the announcer read a prophecy that Stalin had made in 1939 at the end of the Great Purge. "Year by year new generations will arise," the announcer said, imitating Stalin's accent. "They will again raise the banners of their fathers and grandfathers and will restore to us everything we are owed." The crowd roared, and the sky lit up with fireworks.

Since May, when Putin began his third term as President, his declared objective has been to launch a 21st century Russian resurgence. But his rhetorical embrace of Russia's imperial past at home has brought him increasingly into conflict abroad--particularly with the West. Putin tried fitfully during the first decade of his rule to find common ground with the U.S. and its allies. Now he's blithely burning those bridges. The real-world effects of Putin's newly confrontational approach have been most evident in recent weeks with the crisis in Syria. Russian officials have suggested that a U.S. military strike against the Assad regime could lead to a war that would engulf the Middle East and even spread to Russia's southern frontier in the Caucasus. Putin has demanded proof that Assad had used chemical weapons against rebels, telling the Associated Press it was "ludicrous" that the Syrian military would gas its enemies when it already had them on the ropes.