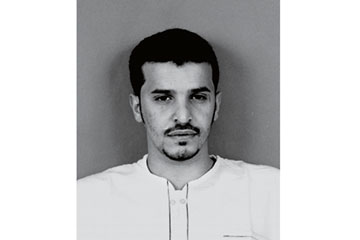

Saudi national Ibrahim al-Asiri has evolved into al-Qaeda's most inventive bombmaker.

(6 of 6)

Some of that success has come from the 71 U.S. drone strikes in Yemen, which the Long War Journal says have killed 349 militants and 82 civilians over 11 years. Some has come from human intelligence. Saudi officials may have contributed to al-Asiri's radicalization during his time in prison, but the kingdom's re-education program has produced two important AQAP defectors, one who stopped the cargo-bomb plot and another who provided details of al-Asiri's operations.

Already some counterterrorism officials are looking past al-Asiri for how to address al-Qaeda's remaining followers. Former CIA and FBI official Philip Mudd, who oversaw the U.S. government's daily assessment of terrorist threats, known as the threat matrix, describes the residual cells like AQAP as sparks from the comet of al-Qaedaism, potentially capable of starting a fire but also just as likely to burn out if left alone. "They pretend to be al-Qaeda, but they look to me more like ... groups that are largely locally focused," Mudd says.

That may be true for much of AQAP and for other small groups from Libya to Mali to South Asia. But it is not true of al-Asiri. The longer he is allowed to operate, the more dangerous he becomes, U.S. officials say. Not only do his designs become harder to stop, but he may also be teaching others his dangerous skills. "There is intelligence that he has unfortunately trained others, and there's a lot of effort to identify those folks," Pistole told the Aspen Security Forum in July. Al-Asiri's most dangerous creation ultimately may not be a bomb but other bombmakers.