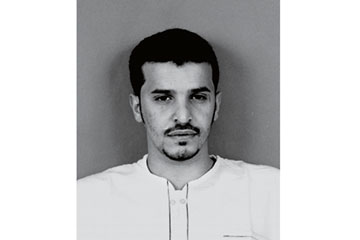

Saudi national Ibrahim al-Asiri has evolved into al-Qaeda's most inventive bombmaker.

(4 of 6)

Al-Asiri deployed the second version within months, this time strapped to a young Nigerian named Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who boarded Northwest Airlines Flight 253 from Amsterdam to Detroit on Christmas Day 2009. Abdulmutallab had been radicalized in Nigeria, then had studied Arabic in Yemen and found his way into AQAP circles there. With a Nigerian passport and no known ties to radicals, he was a perfect choice for al-Asiri's next attempt. But when Abdulmutallab tried to set off his bomb on the Detroit-bound flight, it only partly ignited, burning him but failing to explode. It's still not clear whether the bomb failed or whether Abdulmutallab made an error in trying to set it off. Either way, he was taken into custody on landing in Detroit and has since provided U.S. investigators with details of AQAP's activities. The bomb yielded a positive fingerprint for al-Asiri.

At this point President Obama himself became focused on al-Asiri. First he ordered Brennan to figure out how the Christmas Day plot had gone undetected. In early 2010, Brennan reported that the U.S. could have uncovered the plot with better "correlation of data." In other words, the threat was there for counterterrorism officials to see--for instance, Abdulmutallab's father had tried to bring his son's radicalization to the attention of the U.S. embassy in Nigeria--but they didn't know where to look. In response, the President mobilized countermeasures. First, the TSA increased the number of backscatter scanners it was using from 40 in 19 airports to 385 in 68 airports in under a year. The President instructed 10 different agencies to take steps to address the threat, including ordering the Director of National Intelligence to accelerate "database integration, cross-database searches and the ability to correlate biographic information with terrorism-related intelligence."

But al-Asiri and AQAP were adapting too. In late October 2010, AQAP mailed two printer cartridges to a synagogue and a Jewish center in Chicago from international courier offices in Sana'a. The powdered ink in them had been replaced with powdered explosives. Using cell-phone parts as timers, al-Asiri set the bombs to go off as the planes carrying them in their holds approached the city. The plot was foiled by the defector al-Fayfi, who provided the packages' tracking numbers to Saudi officials, who in turn passed them on to Brennan. Officials in the U.K. and the UAE pulled the packages off FedEx and UPS planes. But al-Asiri's bombs were so well designed that even when the officials pulled the printer cartridges out of the packages they could not detect them. In one case a bomb-sniffing dog failed to alert on the bomb. Only after U.S. officials told their foreign counterparts to go back and look again was the U.K. bomb discovered.