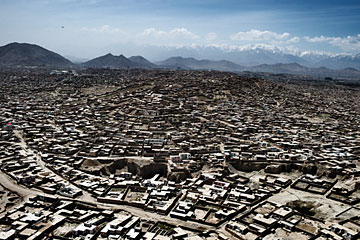

An aerial view of Kabul. The threat of a serious economic reversal is becoming a daily concern

(2 of 3)

The Great Unknown

Nobody really knows what that means, exactly, or what will happen next year when most of the foreign troops go home. Depending on who's talking, Kabulis refer to 2014 with either a sense of dread or teeth-clenched optimism. One thing everyone agrees on, however, is that things are not going to be the same, and you don't have to look hard to see how. HOUSE FOR RENT notices are already ubiquitous throughout the capital. In the center of town, a gated 35-room compound — replete with a sauna, whirlpool and safe room — that a foreign security firm used to rent for $50,000 a month has been empty for a year. (Afghan forces have taken over much private security, so foreign guns are shipping out.) The landlord has dropped the asking price to $20,000 — not exactly a steal, but then again, there is a squash court.

"Three years ago, we were searching for houses," says Naqibullah Sherani, sitting in the customer-free office of Afghanistan Naween Real Estate in Kabul. Sherani helped start the business in 2005 when the city was flush with cash. Now, he says, sales are down by about 40%. International clients aren't renting, and the Afghans who can afford to buy homes — even modest homes, without the facilities to rival a small hotel — aren't investing until they see what happens next year. "We aren't making any money now," Sherani says, "but we'll try to survive."

Real estate is not the only business that's taken a hit. "Investment is down. Private construction is down. Trade is down," says Zakhilwal, the Finance Minister. "In the past year, the morale of the private sector has been severely damaged." In 2012 the number of newly registered firms in Afghanistan dropped by 8%, according to the World Bank. Zakhilwal chalks up the foul mood to fearmongering by politicians and warlords who stand to benefit from seeing Afghanistan return to chaos. But investors and citizens have concerns that are very much grounded in reality. Despite the billions spent in the country, the government still struggles to govern effectively outside Kabul and provide basic services to its citizens, let alone build robust industries and create the hundreds of thousands of jobs that are desperately needed. "There's been such an influx of foreign money, but not enough has been built to soften the blow of that money disappearing," says Barr of Human Rights Watch. Many, including Zakhilwal, complain that most aid money was spent as international donors saw fit and not used to bolster the government's budget. Then again, if aid had been administered by the government, it is unclear how much more of it would have ended up lining officials' pockets.

Foreign aid has, of course, done some good. The past decade has seen dramatic improvements in health care and girls' education in particular, and Afghan forces are now leading security operations in about 90% of the country, according to the U.S. Department of Defense. But security is getting steadily worse as the Taliban have ramped up their attacks ahead of 2014. Parts of the country that used to be safe are now no-go zones.

That leaves the Finance Ministry, and other groups in Kabul that are trying to attract investors, in a quagmire. Less than 20% of the government's total public spending comes from domestic revenue, according to a recent World Bank report. To change that, Afghanistan needs to attract more investment to create the jobs that will help keep frustrated young men from joining up with the Taliban and other militants. But it can't get investors to stay as violence worsens. "You want to establish a sense of personal and economic security so you don't have an instantaneous brain drain, a dramatic loss of middle managers and hence a repeat of what happened under the Taliban," says Ken Yamashita, the mission director for USAID in Afghanistan. "It's one of the things that keeps a lot of us up at night."

Some people have already left — and returned. In the parking lot of an apartment complex in Kabul, Samir Sharefy sits in his dusty Toyota Corolla and looks glumly at a shuttered grocery kiosk. Last year, the 22-year-old sold the small shop when sales started slowing in the increasingly uncertain times. He paid thousands of dollars to a smuggling ring to get him to France, but he got stuck in Greece, where his handlers demanded another $10,000 to take him the rest of the way. Out of cash, Sharefy spent three months in a windowless hotel room before he walked out the door and handed himself over to the police to be deported. "I just wasted everything," Sharefy says. "Every day I keep looking for work, but I can't find anything."