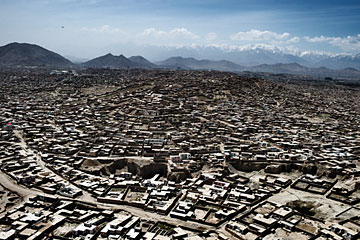

An aerial view of Kabul. The threat of a serious economic reversal is becoming a daily concern

There is something ineffably odd about seeing 400,000 pairs of new boots that may never be worn. In a shuttered wing of the Milli Factory in Kabul, a vast stockpile of tan military footwear sits mothballed in dusty plastic bags, waiting to be shipped off to the soldiers for whom it was made. But after a change in a contract with the U.S. government to provide boots to Afghan security forces, that day may never come. Fawad Saffi, whose father started this factory in 1979, surveys a hulking piece of machinery the family imported from Germany in 2011. "They kept on asking us to improve the quality, so we did," Saffi says. "But then they disappeared."

Three years ago, the Milli Factory was heralded as a symbol of the positive impact NATO troops and their war in Afghanistan were having on the local economy. Now it's a symbol of what's happening as those troops leave. Last year, the U.S. handed much of the responsibility of supplying Afghan forces — along with so many other things — over to Kabul. As contracts changed hands, Milli's shoe production lines ground to a halt. (They still make PVC piping and mattresses.) Hundreds of workers lost their jobs, and the Saffis were left feeling cheated when their contract ended earlier than they'd expected. "In Afghanistan, we have a different way of doing things," says Saffi. "If you make a deal, you make a deal."

Everyone knew it wouldn't last forever. But as foreigners and dollars have begun to make their exit ahead of the withdrawal of international troops next year, a palpable sense of unease has settled over the low-slung Afghan capital. Lucrative contracts that fueled war-dependent businesses like logistics firms and private-security outfits are drying up. As international aid shrinks, thousands of Afghans face losing their jobs — in a country that already has a nearly 50% underemployment rate. The Afghan government recently estimated it would need half a million new jobs to fill the growing gap, but more and more Afghans don't believe those jobs will come in time for them and their families. Many of those who can afford it are packing up and leaving. "One thing everyone is certain about is that there is a massive economic collapse about to happen," says Heather Barr, a researcher for Human Rights Watch in Afghanistan. "Everybody is working on their exit strategies."

Not everyone subscribes to that doomsday scenario. Afghanistan's economy has been on an upward trajectory: real gross domestic product has grown an average of about 10% over the past decade, according to the World Bank. And though the billions of aid and military dollars that have been pumped into the country since the U.S.-led coalition forces invaded it in 2001 are beginning to taper off, the cash flow won't dry up overnight. International donors have pledged to give Afghanistan $16 billion through 2016 that will help the government transition to a peacetime economy, a process Kabul estimates will take about 10 years. There are plenty of people who think that process is less a looming crisis than a return to normality. Afghanistan, they say, has never been a rich country, and the tens of billions of dollars in development aid and military money that has flowed in over the past decade simply created unrealistic expectations. "We should have never expected that the aid would continue," Afghanistan's Minister of Finance Omar Zakhilwal tells TIME. "But the way it was delivered ... created a sense of dependency in the government and among the people. We must break that sense of dependency. And the way to do it is to start to live within our means."