(5 of 5)

Such Euro-arrogance does little to endear the E.U. to ordinary Britons. But much British anxiety about the E.U. is also rooted in misconception and myth. While Brussels does issue the occasionally obtuse diktat, E.U. bureaucrats have never banned bent bananas or legislated to cover barmaids' cleavages or outlawed the Queen's favorite dog breed, the corgi. Such tall tales play to UKIP's narratives, which are interlaced with unease over immigration, a nagging sense that British culture and prosperity are under external threat and a general disillusionment with mainstream politics. Turn away from Europe, UKIP argues, and Britain can go back to being Britain.

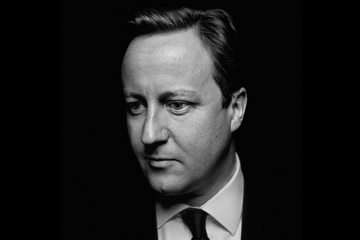

Cameron asserts that he's delivering plenty of other results that should please the right and not a few on the left. His government is recalibrating the core institutions that have defined postwar Britain: the National Health Service, the welfare and pension systems, schools--all long-standing Tory targets. On the other hand, he has championed gay marriage, in the teeth of opposition from his party. On May 21, a bill legalizing same-sex marriage got the assent of the House of Commons--but fewer than half of Conservative MPs.

But it's Cameron's Europe policy that has done the greatest damage to relations with his fellow Conservatives. They never forgave John Major, the last Tory Prime Minister, for signing up to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which turned the single market into the E.U. A revolt among the ranks undermined his leadership. That same rebellious spirit is now abroad in Westminster, where there's talk in the bars and tearooms of Cameron's ouster. The surviving "Big Beasts" of Margaret Thatcher's Cabinet are queuing up to offer damaging commentaries. "The ratchet-effect of Euroskepticism has now gone so far that the Conservative leadership is in effect running scared of its own backbenchers, let alone UKIP," former Chancellor Lord Howe wrote in the Observer.

But even if Cameron were ousted tomorrow, he has set in motion deep changes that won't be easily stopped. His administration is among "the most radical governments anywhere in the Western world," he says, with evident pride, listing as its achievements "very big, meaty reforms" of the public sector. He acknowledges that he didn't have much choice about imposing an economic-austerity program to avoid "massive uncertainty in the financial markets." But he's satisfied with the outcome. "The central government's smaller than it's been at any time since the Second World War," he says.

Another of his decisions could lead to the downsizing of the United Kingdom itself: a plebiscite next year will allow Scotland to choose whether to stay in the U.K. In agreeing to that vote, Cameron gambled that Scots will see that their interests lie in remaining part of a union that provides access to a big internal market and more heft and profile in international affairs than a small country could achieve on its own. Now, if only he can persuade his countrymen--and more immediately, his party--to think that way about Europe.