(2 of 5)

For its part, the U.S. would much prefer that Britain remain in the E.U.: an exit would have not only economic repercussions but also diplomatic ones. Britain has always facilitated U.S. communications with continental Europe, and British leaders have often taken the U.S. side in international debates. With Cameron standing next to him at the White House podium, Obama explicitly backed his British partner's position on Europe. "You probably want to see if you can fix what's broken in a very important relationship before you break it off," he said.

Buoyed by Obama's endorsement, which made headlines back in the U.K., the Prime Minister flew on to Boston and then New York City. There, speaking with a panel of Time Inc. editors, Cameron talked about trade, about attempts to find a settlement in Syria, about Iran--all issues that reinforce his view of the importance of international relationships in a globalized world. Most of all, Cameron talked about Europe. He is combatting an attitude he describes as "a sort of 'Stop the world, I want to get off, pull up the drawbridge' approach to life," he says. "That's not what made Britain great, nor will make us great in the future." Cameron's vision of his island nation is not one of splendid isolation. To be great, he argues, Britain needs Europe.

The Continental Divide

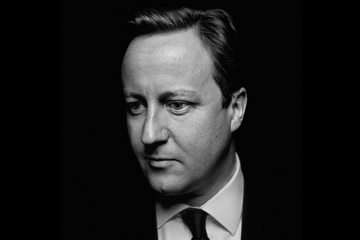

To understand why that view may cost Cameron his leadership--and how the internal politics of Britain's Conservative Party has somehow turned into a matter of global importance--you need to know a little about the party and its tendency to self-destruct over Europe. But first you need to know who Cameron is: a bred-in-the-bone Conservative who has evolved into a political pragmatist.

Descended from King William IV and the grandson of a baronet, David William Donald Cameron was born into Britain's ruling classes; studied at Eton College, an elite school that has produced 19 British Prime Ministers; and took politics, philosophy and economics, the Oxford University degree that has graced the résumés of many Establishment figures. As preparation for a career in politics, these advantages conferred notable disadvantages. Cameron is most comfortable in his own gilded circles and relies on proxies to connect with the masses. This has sometimes had disastrous consequences, as when he appointed as his press chief Andy Coulson, former editor of Rupert Murdoch's tabloid News of the World, a decision that embroiled Cameron in the hacking scandal.

But Cameron's start in life in other respects equipped him admirably to rise. It gave him confidence, fluency, a grounding in the disciplines and traditions of British parliamentary politics and a worldview that sits well with some parts of the Conservative Party. Cameronism is Atlanticist, friendly to big and small business and free trade, fiscally conservative, opposed to Big Government, patriotic, traditionalist. That worldview, much like the Christian faith Cameron once described as "part of who I am" while admitting he was not a regular churchgoer, is a part of his identity that he revisits only occasionally. On a day-to-day, policy-by-policy level, he's prepared to sacrifice small principles for what he regards as bigger ones.