(5 of 7)

The figures are so dazzling that it's tempting to think physicians and CPAP manufacturers are just cashing in. Surely disordered sleep is not just disordered breathing. And yet even researchers with no profit motive agree that the pulmonary system is key to understanding dreams. "The oxygen story is the biggest story here," says Dr. Murali Doraiswamy, head of the division of biological psychiatry at Duke University. "Intuitively, it makes sense. The brain uses a disproportionate amount of oxygen. We think that when the brain is going to sleep, it is shutting down. But oxygen is also going on and off during sleep. That could be a very simple mechanism we've overlooked in the search to explain dreams."

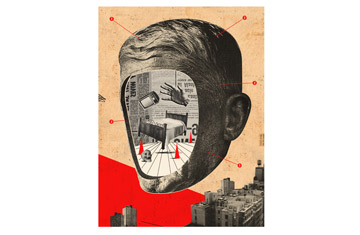

The sleep-apnea explanation is seductive: bad dreams are simply the result of a narrow airway. But the explanation isn't fulfilling. Surely nightmares, with all their marbled psychological tissue, can't just be neurological firings after what amounts to a deep wheeze. If dreams are random physiological events, why can we control their content with IRT? There's also the phenomenon of lucid dreaming--being able to realize you're dreaming and then control the dream as it occurs. From a fellow nightmare sufferer in New York, I had heard about a way to train yourself to dream lucidly--an approach that combines psychological and physiological techniques to enter bad dreams as they occur and rewrite them. It sounded silly, as if someone were trying to turn the movie Inception into real life. But it was also a really cool idea.

Reformulating Your Dreams

Stephen Laberge often wears a puckish grin, which goes nicely with his white hair that stands on end as though he's been electrocuted. In 1980, LaBerge earned a Ph.D. in psychophysiology--the study of how the body, brain and mind interact. In the years since, especially when teaching at Stanford, he has become something of a dream guru. He believes that dreams aren't walled off from daytime life but are as manageable as any other behavioral experience.

LaBerge is the leading figure behind the idea of lucid dreaming. Clients from around the world seek his help in trying to control their bad dreams. LaBerge and I met at the Newport Beach, Calif., house of one of those clients, Edward Pope, who told me he is an investor in aerospace and other technologies. His opulent home sits behind a gate on a hill overlooking the Pacific.

At Stanford, LaBerge became convinced that the question of whether dreams are physiological or psychological is not only unanswerable but also irrelevant. He posited that if people practice dream recall--writing in a dream journal morning after morning--they can begin, while asleep, to recognize when they are dreaming. "Dreams and waking experiences are more alike than different," he wrote in his 2004 book Lucid Dreaming. "Much of what happens during your night life will be little different from what happens during your day life."