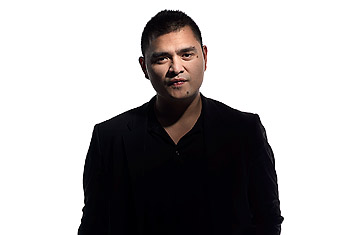

Jose Antonio Vargas

(7 of 9)

But perception has become reality. What's cemented in people's consciousness is the television reel of Mexicans jumping a fence. Reality check: illegal border crossings are at their lowest level since the Nixon era, in part because of the continued economic slump and stepped-up enforcement. According to the Office of Immigration Statistics at DHS, 86% of undocumented immigrants have been living in the U.S. for seven years or longer.

Still, for many, immigration is synonymous with Mexicans and the border. In several instances, white conservatives I spoke to moved from discussing "illegals" in particular to talking about Mexicans in general — about Spanish being overheard at Walmart, about the onslaught of new kids at schools and new neighbors at churches, about the "other" people. The immigration debate, at its core, is impossible to separate from America's unprecedented and culture-shifting demographic makeover. Whites represent a shrinking share of the total U.S. population. Recently the U.S. Census reported that for the first time, children born to racial- and ethnic-minority parents represent a majority of all new births.

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, there are also at least 17 million people who are legally living in the U.S. but whose families have at least one undocumented immigrant. About 4.5 million U.S.-citizen kids have at least one undocumented parent. Immigration experts call these mixed-status families, and I grew up in one. I come from a large Filipino clan in which, among dozens of cousins and uncles and aunties and many American-born nieces and nephews, I'm the only one who doesn't have papers. My mother sent me to live with my grandparents in the U.S. when I was 12. When I was 16 and applied for a driver's permit, I found out that my green card — my main form of legal identification — was fake. My grandparents, both naturalized citizens, hadn't told me. It was disorienting, first discovering my precarious status, then realizing that when I had been pledging allegiance to the flag, the republic for which it stands didn't have room for me.

'Why did you come out?'

asked 20-year-old Gustavo Madrigal, who attended a talk I gave at the University of Georgia in late April. Like many Dreamers I've met, Madrigal is active in his community. Since he grew up in Georgia, he's needed to be. A series of measures have made it increasingly tough for undocumented students there to attend state universities.

"Why did you come out?" I asked him in turn.

"I didn't have a choice," Madrigal replied.

"I also reached a point," I told him, "when there was no other choice but to come out." And it is true for so many others. We are living in the golden age of coming out. There are no overall numbers on this, but each day I encounter at least five more openly undocumented people. As a group and as individuals, we are putting faces and names and stories on an issue that is often treated as an abstraction.