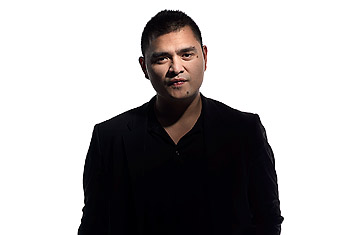

Jose Antonio Vargas

(2 of 9)

I've also been witness to a shift I believe will be a game changer for the debate: more people coming out. While closely associated with the modern gay-rights movement, in recent years the term coming out and the act itself have been embraced by the country's young undocumented population. At least 2,000 undocumented immigrants — most of them under 30 — have contacted me and outed themselves in the past year. Others are coming out over social media or in person to their friends, their fellow students, their colleagues. It's true, these individuals — many brought to the U.S. by family when they were too young to understand what it means to be "illegal" — are a fraction of the millions living hidden lives. But each becomes another walking conversation. We love this country. We contribute to it. This is our home. What happens when even more of us step forward? How will the U.S. government and American citizens react then?

The contradictions of our immigration debate are inescapable. Polls show substantial support for creating a path to citizenship for some undocumenteds — yet 52% of Americans support allowing police to stop and question anyone they suspect of being "illegal." Democrats are viewed as being more welcoming to immigrants, but the Obama Administration has sharply ramped up deportations. The probusiness GOP waves a KEEP OUT flag at the Mexican border and a HELP WANTED sign 100 yards in, since so many industries depend on cheap labor.

Election-year politics is further confusing things, as both parties scramble to attract Latinos without scaring off other constituencies. President Obama has as much as a 3-to-1 lead over Mitt Romney among Latino voters, but his deportation push is dampening their enthusiasm. Romney has a crucial ally in Florida Senator Marco Rubio, a Cuban American, but is burdened by the sharp anti-immigrant rhetoric he unleashed in the primary-election battle. This month, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on Arizona's controversial anti-immigrant law. A decision either way could galvanize reform supporters and opponents alike.

But the real political flash point is the proposed Dream Act, a decade-old immigration bill that would provide a path to citizenship for young people educated in this country. The bill never passed, but it focused attention on these youths, who call themselves the Dreamers. Both the President and Rubio have placed Dreamers at the center of their reform efforts — but with sharply differing views on how to address them.

ICE, the division of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) charged with enforcing immigration laws, is its own contradiction, a tangled bureaucracy saddled with conflicting goals. As the weeks passed after my public confession, the fears of my lawyers and friends began to seem faintly ridiculous. Coming out didn't endanger me; it had protected me. A Philippine-born, college-educated, outspoken mainstream journalist is not the face the government wants to put on its deportation program. Even so, who flies under the radar, and who becomes one of those unfortunate 396,906? Who stays, who goes, and who decides? Eventually I confronted ICE about its plans for me, and I came away with even more questions.