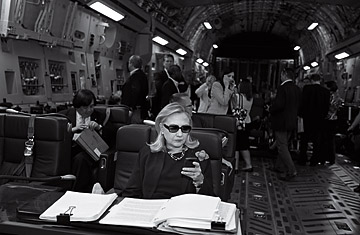

Clinton aboard a C-17, on her way to meet with rebel leaders in Tripoli.

Libya

Doesn't much look like a rousing red, white and blue win when you see it at street level. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton disembarked from her C-17 Globemaster III in Tripoli on Oct. 18 and was greeted by a ragtag honor guard of victorious rebels in mismatched uniforms who then trailed her through empty, trash-strewn streets, swerving in and out of her motorcade, pointing their AK-47s into the air. At raucous, fly-infested meetings, Clinton pushed rebel leaders to round up the thousands of missing shoulder-launched missiles that pose a lethal threat to every passenger plane in the region. Even the conflict's finale, which came two days later with the bloody, lawless shooting of the fallen dictator Muammar Gaddafi in his hometown of Sirt, suggested that vengeful chaos may rule, at least for a while, in Libya.

But this may just be what an American victory looks like in the 21st century. Not brass bands and treaties on parchment but unruly insurgents and a promise (fingers crossed) to hold elections. It's fitting that the U.S.-led intervention has yielded a messy and uncertain result; from the start, the mission was as much about the limits of American power as about its expanse. To build support for allied attacks on Gaddafi's troops last March, Clinton had to get Arab leaders behind the mission, convince Congress that other countries would bear most of the cost and placate the Pentagon by arranging for a quick handover of military command to NATO. While in public Clinton was buoyantly optimistic about Libya's future during her visit, in private she was darker. At dusk at the end of her long day in Libya, she spoke at the new U.S. embassy in Tripoli--the previous one was ransacked by pro-Gaddafi forces--and as she talked, there was celebratory gunfire in the background. With a smile, she said, "Someone should tell them not to waste ammunition."

If conserving one's power is on Clinton's mind these days, it is partly because the seven-month Libyan war is a potent metaphor for her broader agenda: creating a 21st century statecraft for a world where social media and instant communication have empowered people relative to their rulers, a world where U.S. influence is limited not only by the rise of loosely networked individuals like al-Qaeda and fast-rising states like China but also by America's economic challenges and the public's lukewarm interest in foreign adventures. Yet a new era of diffuse threats abroad and weak central governments everywhere offers opportunities as well as obstacles for the U.S. to advance its interests. Through a smart combination of its still dominant military hard power and its subtler soft power in economics, development and technology, American influence is being remade in the 21st century. "All power has limits," Clinton told Time as she flew to Afghanistan the day after her Tripoli visit. "In a much more networked and multipolar world," she said, "we can't wave a magic wand and say to China or Brazil or India, 'Quit growing. Quit using your economies to assert power' ... It's up to us to figure out how we position ourselves to be as effective as possible at different times in the face of different threats and opportunities."