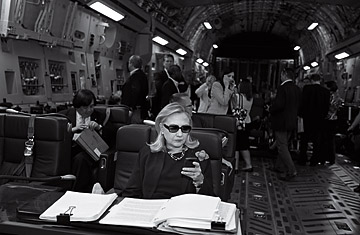

Clinton aboard a C-17, on her way to meet with rebel leaders in Tripoli.

(5 of 6)

Whereas U.S. envoys once filed secret cables to Washington late at night, Clinton has pushed her ambassadors to expand the use of Twitter and Facebook--State now has 192 Twitter feeds and 288 Facebook accounts--and her daughter Chelsea calls her TechnoMom. "We are in the age of participation," Clinton said at her husband's charity event in New York City in September, "and the challenge ... is to figure out how to be responsive, to help catalyze, unleash, channel the kind of participatory eagerness that is there."

Clinton is trying to ensure these changes are permanent: she requires every diplomat who rotates through the foreign-service institute to get training in social media. But most of her novel initiatives are run out of her office, giving them clout now but leaving their survival to the discretion of her successor. Most of these offices have little--or no--independent budget, and some are long on jargon and short on deliverables. Her senior adviser for innovation, Alec Ross, 39, says things like "We're reorienting the foreign-service exam to emphasize dynamic problem-solving skills that help respond to edge-of-network challenges," while the office of her special representative to Muslim communities, Farah Pandith, talks up outreach programs but then admits they have a budget of $0.00. (That's zero.)

Clinton has touted development as a tool of national strategy, spending $8 billion last year on global health and boosting public diplomacy funds for the U.S. embassy in Pakistan from $2 million to $50 million to get recognition for the billions in aid the U.S. has spent there. But foreign aid successes in places like Afghanistan are mixed at best. Though he is a vocal supporter of Clinton, Vermont Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy, who chairs the Appropriations Subcommittee on Foreign Operations, says, "Development projects have been launched on a scale that cannot possibly be sustained ... They have had to continually adjust goals and revise strategy and redefine what success is." And crisis management eats up a lot of the department's energy: Clinton's deputy for management, Tom Nides, says his primary assignment is trying to prepare the State Department to run the mission in Iraq come Jan. 1, 2012, when U.S. troops pull out. Though security assistance will be State's job, an audit released in late October by the special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction found the department had no full assessment of the needs of Iraq's large police force, no benchmarks for progress and no way to track costs. "This audit raises serious questions regarding the [police-training program's] long-term viability," the report concluded.

Paradoxically, Clinton gets high marks on her traditional diplomacy. For her improving of relations with Russia, which yielded support for Iran sanctions and the abstention during the Libya vote, and her measured resistance on China, she has gained a private cheering section within the centrist wing that dominated the foreign policy of George H.W. Bush. "She's been a good Secretary of State," says the dean of American diplomacy, Brent Scowcroft, the first President Bush's National Security Adviser. "She is confident but not arrogant in her confidence, and quite agile," Scowcroft says.

What's Next?