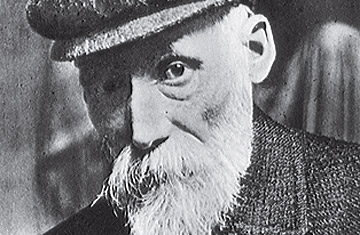

Renoir in 1885, after his turn away from Impressionism

(2 of 3)

For Renoir, a turning point came during his honeymoon to Rome and Naples in 1881. Face to face with the firm outlines of Raphael and the musculature of Michelangelo, he lost faith in his flickering sunbeams. He returned to France determined to find his way to lucid, distinct forms in an art that reached for the eternal, not the momentary. By the later years of that decade, Renoir had lost his taste for the modern world anyway. As for modern women, in 1888 he could write, "I consider that women who are authors, lawyers and politicians are monsters." ("The woman who is an artist," he added graciously, "is merely ridiculous.")

Ah, but the woman who is a goddess--or at least harks back to one--that's a different matter. It would be Renoir's aim to reconfigure the female nude in a way that would convey the spirit of the classical world without classical trappings. Set in "timeless" outdoor settings, these women by their weight and scale and serenity alone--along with their often recognizably classical poses--would point back to antiquity.

For a time, Renoir worked with figures so strongly outlined that they could have been put down by Ingres with a jackhammer. By 1892, the year with which the LACMA show starts, he had drifted back toward a fluctuating Impressionist brushstroke. Firmly contoured or flickering, his softly sculpted women are as full-bodied as Doric columns. This was one of the qualities that caught Picasso's eye, especially after his first trip to Italy, in 1917. He would assimilate Renoir alongside his own sources in Iberian sculpture and elsewhere to come up with a frankly more powerful, even haunting, amalgam of the antique and the modern in paintings like Woman in a White Hat.

That picture is in the LACMA show, along with works by Matisse, Bonnard and Maillol, to demonstrate Renoir's influence. What's apparent from these, however, is that Renoir was most valuable as a stepping-stone for artists making more potent use of the ideas he was developing. The heart of the problem is the challenge Renoir set for himself: to reconcile classical and Renaissance models with the 18th century French painters he loved. To synthesize the force and clarity of classicism with the intimacy and charm of the Rococo is a nearly impossible trick. How do you cross the power of Phidias with the delicacy of Fragonard? The answer: at your own risk--especially the risk of admitting into your work the weaknesses of the Rococo. It's a fine line between charming and insipid, and 18th century French painters crossed it all the time. So did Renoir.

The Artist in Winter

In the late 1890s, renoir developed rheumatoid arthritis. It progressed until his fingers were bent into claws, the tips pressed against the palms of his hands. On the recommendation of his doctors, he moved from Paris to the dry climate of Provence, where, like so many other artists, he found a personal paradise, a garden tended by ghosts of the ancient Mediterranean. His was a farmstead in Cagnes-sur-Mer, not far from Nice. Though in constant pain, Renoir entered the most productive period of his career, producing hundreds of canvases, many of them painted while he could barely grip a brush.