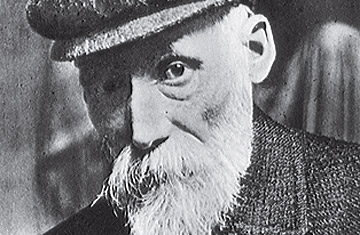

Renoir in 1885, after his turn away from Impressionism

Some artists go out in a blaze of glory. Titian is an obvious example: his dark, sketchy late work would be influential for centuries. Van Gogh is another: The Starry Night was produced by a man who would take his own life the following year. Pierre-Auguste Renoir went out in a blaze of kitsch. At least, that's the received opinion about the work of his final decades: all those pillowy nudes, sunning their abundant selves in dappled glades; all those peachy girls, strumming guitars and idling in bourgeois parlors; all that pink. In the long twilight of his career, the old man found his way to a kissable classicism that modern eyes can find awfully hard to take.

The determined-to-change-your-mind new show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is called "Renoir in the 20th Century." It could just as well have been called "Renoir: The Problem Years." Take one look at a painting like Bather Sitting on a Rock, and the problem is obvious: cupcakes don't get much more scrumptious than this. Which is another way of saying that a whole line of mildly lubricious babes, from the phosphorescent nymphs in Maxfield Parrish to Tinkerbell and the Playboy bunny, owe something to the old man's influential wet dream of classical form. All the same, the Renoir of this period--three very productive decades before his death in 1919 at the age of 78--fascinated some of the chief figures of modernism. Picasso was on board; his thick-limbed "neoclassical" women from the 1920s are indebted to Renoir. So was Matisse, who had one eye on Renoir's Orientalist dress-up fantasies like The Concert, with its flattened space and overall patterning, when he produced his odalisques. Given that so much of late Renoir seems saccharine and semicomical to us, is it still possible to see what made it modern to them?

Yes and no. To understand the Renoir of "Renoir in the 20th Century," which runs in Los Angeles through May 9 then moves to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, you have to remember that before he became a semiclassicist, he was a consummate Impressionist. You need to picture him in 1874, 33 years old, painting side by side with Monet in Argenteuil, teasing out the new possibilities of sketchy brushwork to capture fleeting light as it fell across people and things in an indisputably modern world.

But in the decade that followed, Renoir became one of the movement's first apostates. Impressionism affected many people in the 19th century in much the way the Internet does now. It both charmed and unnerved them. It brought to painting a novel immediacy, but it also gave back a world that felt weightless and unstable. What we now call post-Impressionism was the inevitable by-product of that anxiety. Artists like Seurat and Gauguin searched for an art that owed nothing to the stale models of academicism but possessed the substance and authority that Impressionism had let fall away.