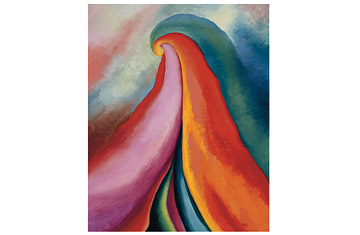

Series I, No. 4, 1918. O'Keefe's oils drew from nature, Art Nouveau and her interior life.

(2 of 2)

For Kandinsky, the horsemen in Blue Mountain had a symbolic meaning as emblems of expressive freedom. In 1911, when he formed an artists' group with Franz Marc, Alexei Jawlensky and a few other like-minded painters, they called it the Blue Rider. (Blue signified spirituality to him.) And by that year, with his succinctly titled Picture with a Circle, Kandinsky was galloping full speed in the direction of complete abstraction. But for him, abstract images were also representations of a kind, correlatives of spiritual realities. He was an admirer of the Russian mystic Madame Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, a stew of beliefs about a spiritual realm that would someday replace the material world. Though Kandinsky's dedication to Theosophy is a familiar part of his biography, the Guggenheim show, which continues through Jan. 13, is largely silent on the matter. Has it all gotten to be too embarrassing? Without bringing it into the story, you can't fully grasp how Kandinsky, author of Concerning the Spiritual in Art, saw his work as a search for forms and colors that would speak the language of that higher plane.

O'Keeffe, who owned a copy of Kandinsky's book, was no Theosophist, but like him, she felt that abstract art could express the artist's purely internal realities. In 1915 she was a 28-year-old art teacher stuck at a small women's college in South Carolina. One year earlier, she had been living happily in New York City and getting her first eager taste of Picasso, Braque and American modernists like John Marin. Stranded in a place she called the "tail end of the world," she decided to go where none of those artists had ventured. Drawing on the liquid forms of Art Nouveau and her own churning inner life, she produced an astonishing series of purely abstract charcoal drawings, some of the most radical work being done anywhere at that moment.

We would probably know nothing of those drawings today if O'Keeffe hadn't mailed some to a friend in New York who took them to the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, a pivotal figure in the small world of American modernism. Stieglitz agreed to include them in a group show at his 291 gallery, the tiny cockpit of advanced art where O'Keeffe had seen those Picassos and Marins. They were an immediate hit. Two years later, he gave her a solo exhibition that made her name for good.

By that time, O'Keeffe had reintroduced color into her work. Her typical canvases were eruptions of soft form, like the cresting fiddleheads of mauve, orange and green in Series I, No. 4, from 1918. But she also worked in a taut, sharp-edged register that produced work like Red & Orange Streak, from the following year. Nothing about a picture like that suggests it's the work of a woman, but from early on, critics treated her paintings as bulletins from the Eternal Feminine. In her plump bulbs of color and shadowy openings they found the swells and inlets of the female body. Or as Paul Rosenfeld put it, "What men have always wanted to know and women to hide, this girl puts forth." Things got only worse after Stieglitz, who would become her lover and then her husband, exhibited his intimate nude photographs of her in 1921, pictures that marked her forever as the pinup girl of the avant-garde.

Let's grant that a lot of O'Keeffe's work invites those readings. When you're faced with the labial purple coils of a painting like Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, from 1918, what else can you think about? But what's so refreshing about the Whitney show — which runs through Jan. 17, then moves to Washington and Santa Fe, N.M. — is the way it spares us O'Keeffe the Earth Mother and points us back to the endlessly inventive formalist she remained, intermittently, to the end of her life.

Abstraction may not be a religion anymore, but you can't look at the early buoyant pictures in either of these shows without being glad that, for a while, there were artists who kept the faith.