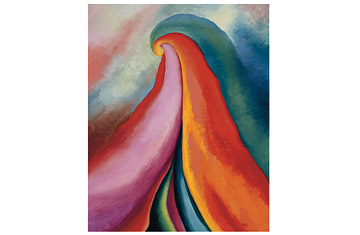

Series I, No. 4, 1918. O'Keefe's oils drew from nature, Art Nouveau and her interior life.

It's been a long time since abstract art was a religion. For most artists now, it's just an option, a mode they can pursue or ignore as it suits them. But once it was a passion, a polemic, a faith. Wassily Kandinsky, one of its founders, could talk about geometric forms as though they were sacred images — and to him, they were. In a burst of high feeling he could argue, with a straight face, that "the contact between the acute angle of a triangle and a circle has no less effect than that of God's finger touching Adam's in Michelangelo." They just don't make triangles like that anymore.

By a happy coincidence of programming, two of New York City's biggest museums are looking back this fall on those exalted beginnings. "Kandinsky," at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, sends nearly 100 of the artist's works up the Guggenheim's spiral ramp like a whirlpool of angels in a Tiepolo ceiling. Meanwhile, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, "Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction" scrapes away O'Keeffe's barnacled legend as the Gray Lady of New Mexico to recall the young woman who at the dawn of abstraction made a fearless leap into the unknown.

Like airplanes and antibiotics, abstract art is one of the defining inventions of the 20th century. But it's hard to say who arrived first at pure abstraction — images with no reference to the visible world — because abstraction is also one of those things, like calculus in the 17th century and photography in the 19th, that germinated in several places at about the same time.

In this case the time was the years just before and after the start of the First World War, in 1914. That was when the multidirectional Czech painter Frantisek Kupka and the austere Russian Kazimir Malevich were in their different ways achieving escape velocity on canvas. And so was Kandinsky, who would become the most tireless apostle of an art that answered to nothing in the merely material world. Born in 1866 to a prosperous Moscow family, Kandinsky spent his 20s studying law and economics, all the while bending toward another calling. He was the sort of young man who could be sent into ecstasies by a sunset. "The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot," was how he described one years later, "which, like a wild tuba, sets all one's soul vibrating." A wild tuba? So much for law and economics.

In 1896, Kandinsky, with his first wife Anja, decamped to Munich to become an artist and art teacher. His early paintings were folkloric, storybook scenes of an imaginary medieval Russia rendered like mosaics in bright lozenges of color. It wasn't until the summer of 1908, when he discovered the little town of Murnau in the Bavarian Alps, that he began to uncouple his pictures from any sources in the visible world. In Blue Mountain, which he began the following winter, he assigned the mountain an unearthly shade of indigo and turned the flanking trees into almost free-floating pools of pigment. With one eye on the crackling Fauvist pictures that Henri Matisse and André Derain had exhibited in Paris a few years earlier, he was on the way to letting form and color alone become the subject of his work.