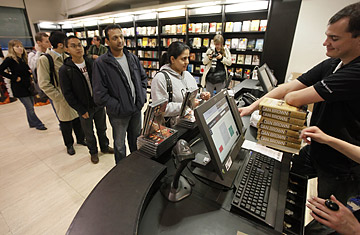

People line up to buy Dan Brown's latest book, The Lost Symbol, in London on Sept. 15, 2009

Somebody out there has probably already pointed out that the publication date of The Da Vinci Code--March 18, 2003--came just two days before the American invasion of Iraq. That isn't a conspiracy; it's just a coincidence. But it does, as fans of The Da Vinci Code say, make you think.

Consider: Dan Brown's novel proposed an alternative history of Christianity, wherein a bitter schism took place shortly after Jesus' death between the mean patriarchal faction that concealed Jesus' marriage and the nice faction of startlingly liberal first-wave feminists. In other words, The Da Vinci Code recast the history of Christianity into something that looks a lot more like the history of ... Islam, wherein a bitter early schism took place between the Sunnis and the Shi'ites. Could the book's passionate following in predominantly Christian America express a repressed longing for a sexier, darker, more exciting history--like the Muslims have? Who cares about the Diet of Worms? Wouldn't it be cool if Jesus got his Grail on?

Probably not. But that's the name of the game in the Browniverse: coincidences aren't just chance, and things aren't just things; they mean something. Brown's hero, Robert Langdon, is after all a professor of symbology (a branch of human inquiry that--it cannot be stated often enough--doesn't exist, at Harvard or anywhere else). Beneath his learned, oddly asexual caress, objects come to life and become symbols. A V isn't just a V--it's a chalice, a symbol of the eternal feminine. Noise becomes signal. Chaos becomes order.

Unlike the first two Langdon novels, which dealt with the Christian church, The Lost Symbol (Doubleday; 509 pages) deals with the Freemasons (whose motto, "Ordo ab chao"--order out of chaos--could be his own). In the opening pages, Langdon is summoned--he's always getting summoned--to Washington by a call that he thinks is from his old mentor Peter Solomon, head of the Smithsonian. Langdon believes he's to give a speech at a fundraiser. But when he shows up, there's no fundraiser and no speech, just Solomon's severed hand, grotesquely tattooed, stuck on a spike in the Capitol rotunda. Oh, snap.

At this point, Brown's signature touches are already in place. Langdon is present and accounted for: Mickey Mouse watch, check; tweed jacket, check; freakish memory, check; crippling claustrophobia, check. We've also been introduced to a lonely, violent fanatic with weird skin. His name is Mal'akh, not Silas, and instead of being an albino, he's covered in tattoos--but same difference.

It's easy to run Brown down because his writing isn't exactly deft. The unfortunate sentence "His massive sex organ bore the tattooed symbols of his destiny" should itself be forcibly tattooed on Brown's massive sex organ. His scholarship reads like the work of a man who believes Wikipedia. In particular, the book suffers from an ill-advised fling with something called noetic science, which is based on the idea that human consciousness can affect the physical world, thereby providing "the link between modern science and ancient mysticism."