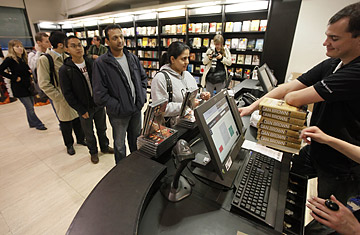

People line up to buy Dan Brown's latest book, The Lost Symbol, in London on Sept. 15, 2009

(2 of 2)

But the general feel, if not all the specifics, of Brown's cultural history is entirely correct. He loves showing us places where our carefully tended cultural boundaries--between Christian and pagan, sacred and secular, ancient and modern--turn out to be messy. Langdon is correct in pointing out that the Capitol "was designed as a tribute to one of Rome's most venerated mystical shrines," the Temple of Vesta, and that it prominently features a painting of George Washington dressed as Zeus. That stuff is deeply weird and not at all trivial. Power is power, and it flows from religious vessels to political ones with disturbing ease. ("That hardly fits with the Christian underpinnings of this country," harrumphs a bystander. Well, right.)

The plot of The Lost Symbol churns forward with a brutalist energy that makes character but a flesh appendage on its iron machine. Langdon must ransack the Capitol for his missing friend, the one who lost the hand, and for a hidden Masonic pyramid, which is the key to the mystical wisdom that will turn man into god--something Mal'akh, the tattooed nut job, has a keen interest in. Langdon is joined by Solomon's sister, another of Brown's interchangeable, "attractive, dark-haired" brainy-hotty heroines, who happens to be a noetic scientist.

Brown continues his zero-sexual-tension policy in The Lost Symbol. Will we never learn what symbols adorn Langdon's sex organ? Instead, Langdon directs his energies toward decoding exotic symbological specimens with an inexhaustible sense of wonderment. (No! It can't be! Oh, but it can, Professor Langdon.) If the book has a human heart, it's the struggle between Langdon's native academic skepticism and the ever mounting evidence that there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in his symbology. "You, like many educated people, live trapped between worlds," a wise priest (he's also a Mason!) tells him. "Your heart yearns to believe ... but your intellect refuses to permit it." Langdon should get together with Agent Mulder from The X-Files.

But Brown has another agenda in The Lost Symbol, which is to place Washington among the great world capitals of gothic mystery, alongside Paris and London and Rome--or, for that matter, Baghdad. What he did for Christianity in Angels & Demons and The Da Vinci Code, he is now trying to do for America: reclaim its richness, its darkness, its weirdness. It's probably a quixotic effort, but it's a touchingly valiant one. We're not just overweight tourists in T-shirts and fanny packs, he seems to be saying. Our history is as sick and strange as anybody's! There's signal in the noise, order in the chaos! You just need a degree from a nonexistent Harvard department to see it.