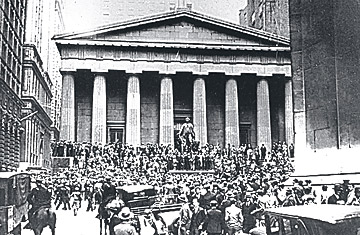

Stocks fell off what Irving Fisher had called a "permanently high plateau" in October 1929 and didn't return until that level until 1954.

(3 of 4)

Upon that basis, economists and finance scholars cleared the way in the 1970s for a new approach to investing and risk management that included index funds, risk-weighted portfolio allocation and mathematical models to price options and other derivatives. A lot of this was, as with Fisher's economics, useful. But a basic assumption underlying much of it--that prices were reliable reflections of economic reality--was problematic.

It didn't take long for a new generation of scholars, many with roots at Samuelson's MIT, to start pointing out the problems. Samuelson protégé Joseph Stiglitz showed that a perfectly efficient market was impossible, because in such a market, nobody would have any incentive to gather the information needed to make markets efficient. Another Samuelson student, Robert Shiller, documented that stock prices jumped around a lot more than corporate fundamentals did. Samuelson's nephew Lawrence Summers demonstrated that it was impossible (without a thousand years of data) to tell a rationally random market from an irrational one.

Shiller and Summers in particular came to revel in tweaking the rational-market establishment. Shiller declared in 1984 that the logical leap from observing that markets were unpredictable to concluding that prices were right was "one of the most remarkable errors in the history of economic thought." Summers described how financial markets were often dominated by "idiots" (he later dubbed them "noise traders" and co-authored a series of academic papers showing how their errors could move prices) and lamented at the 1984 meeting of the American Finance Association that "virtually no mainstream research in the field of finance in the past decade has attempted to account for the stock-market boom of the 1960s or the spectacular decline in real stock prices during the mid-1970s."

The 1987 stock-market crash gave Shiller and Summers all the ammunition they needed. "If anyone did seriously believe that price movements are determined by changes in information about economic fundamentals," Summers said just after the crash, "they've got to be disabused of that notion by Monday's 500-point movement." The crash also demonstrated that prices didn't follow the statistical model of a random walk--if they did, a 20% one-day market drop like that of 1987 should happen only once in billions upon billions of years.

Subsequent years saw more challenges to the core assumptions of the rational market. Even Fama retested his 1969 efficient-market hypothesis and found it wanting. But the strong performance of the U.S. stock market and economy tended to silence doubts about the wisdom of the market both on campus and where it really mattered--in Washington and on Wall Street. Shiller warned repeatedly of irrational exuberance in stocks in the late 1990s and in housing in the early 2000s. He was largely ignored both times--until he turned out to be right. Unwillingness to countenance the possibility that market prices might be wildly wrong defined the behavior of regulators, corporate executives and most Wall Streeters during both the tech-stock and real estate bubbles.